HIS OWN SOCIETY (Ⅲ)MARRIAGE

Masanori YOSHIOKA

INTRODUCTION

This is the third part of an English translation of a hand-copied book

which was written in the “Raga”language by the late Rev. David Tevimule in

1966. “Raga”is a language spoken by the people of North Raga (northern part

of Raga or Pentecost Island) in Vanuatu. The work consists of twenty chapters,

which cover various aspects of North Raga culture: its origin myth, kin

relations, graded system, chiefs, initiation rite and customs ranging from

birth, marriage, to death. In this paper I translate Chapters 8 and 9 in

which Rev. David Tevimule describes customs concerning marriage.(1) Although

he starts his description from the birth of a girl and refers to the custom

of so-called infant betrothal, his main concern is on the marriage ceremony.

Ⅰ

Here I present some materials concerning marriage ceremony which were

collected during my field researches. Marriage ceremony is classified into

two kinds, one of which is called kastom marit (custom marriage) in Bislama

(Vanuatu pidgin) and the other of which is jos marit (church marriage). Kastom

marit is usually referred to as lagiana in Raga language and is thought to be

based on halan lagiana (the road of the marriage) which has been practiced from

before. I will describe this kind of marriage ceremony, which I tentatively

call traditional. It is equal in major points to the ceremony which is

described by Rev. Tevimule but is different in some minor points.

A traditional marriage ceremony is composed of three stages. The first stage

is held on the day before marriage in the village of the bride and the bridegroom

respectively. This is the pre-stage of the marriage ceremony. In each side

they prepare for the day of marriage. The second stage is held in the village

of the bride on the day of marriage. At this stage, people of the bridegroom's side

take the bride and her belongings to the village of the bridegroom. After the

second stage, all the attendants move to the village of the bridegroom, where the

third stage is held. Here the bride wealth is bestowed to the bridegroom.(2)

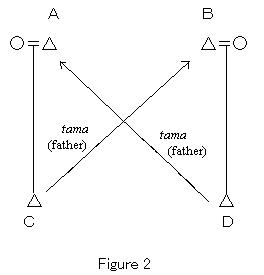

In this way, the people of the bride's side as well as those of the

bridegroom's side lastly come together to the village of the bridegroom, where

the big banquet is given. The people of the bride which is called atatun vavine

(the side of the woman) are composed of the tama (father) of the bride, her

vwavwa (father's sister), the bride's cluster members, and her moiety members other

than the bridegroom's tama and vwavwa.(3) The same classification is also applied

to the people of the bridegroom (atatun mwalanggelo:the side of the young boy). Those

people are entertained with a lot of kava and meals cooked in the earth-oven in the

banquet, which is managed by the real father of the bridegroom.

Kava is a beverage prepared from the roots of the plant with the same

name (Piper methysticum). Kava is usually planted in the field far away from the

village. It is not an easy work to bring a lot of kava roots from the field

to the village. This is, however, just an initial step to produce a kava drink.

There remains the process to prepare a beverage from its roots. First, kava

roots are cut into small pieces. Then you pick a handful of these pieces with the

left hand and a serrated stone with the right hand. The kava pieces are thus

grounded and twisted by both hands. A little water is added to the smashed kava

roots and they are kneaded. Some amount of liquid comes out from squeezing these

kneaded roots. It is not drinkable yet. It becomes drinkable when it is

filtered by a sheet of coconut fiber and is served in a coconut cup.(4)

The food in the earth-oven is called vwavwaligi. When vwavwaligi is

made, first of all, you have to have many stones burned by firewood in the

earth-oven. After the stones are well heated, they are removed from the oven. Then

leaves of heliconia (Heliconia indica) are laid on the heated bottom of the earth-

oven, and raw foods wrapped up in the same leaves are put on them. After the oven

is filled with foods, they are covered again with these leaves. Finally, the heated

stones, which have been removed from the oven in the prior step are put on these

leaves . When the stones cool down after several hours, the cooking is

finished. Vwavwaligi is a kind of baking in a casserole. In this way, vwavwaligi

requires many stones to be burned, a lot of pieces of firewood which burn stones,

and leaves of heliconia by which the ingredients are wrapped. The classificatory

fathers and father's sisters of the bridegroom are asked to fetch firewood from

the field, to bring stones to be burned from the stone ground one can find such

kind of stones, to bring leaves from the field, and so on.

Here is an example to illustrate this procedure. Suppose that the marriage

ceremony is held at A village and a man of B village (who is a classificatory

father of the bridegroom) is requested to fetch firewood for earth-oven. The date

of the works is fixed by the real father of the bridegroom. On the day, this man

sets to work with the assistance of the people of B village. The firewood is cut

down from the field owned by the people of B village. The field which has a lot of

pieces of firewood and is near A village is selected. They start to work in the

morning. The lunch is served in A village. Since the other works such as collecting

leaves, bringing stones, and so on are also done on the same day, a lot of people

who come from several villages in North Raga eat lunch in A village. After lunch,

they work again till evening when they go back to A village. In the village, kava

and supper are prepared by the people of A village. People who finished working are

served to drink kava. After drinking kava, each of them is given a basket filled

with meals (taro or yam and meats etc.) for supper and they go back to their own

village with these baskets.

Through the marriage ceremony, there are two kinds of North Ragan wealth,

which play important roles, that is, big red mat and pig. There are four kinds of

mat in North Raga. One is a big white mat called bwanmaita which is woven of

pandunus leaves. Another is a big red mat called bwanmemea which is the

bwanmaita dyed red. Bwanmemea is often referred to as simply bwana. Another

mat is a small white mat called barimaita which is also woven of pandanus

leaves. The other mat is a small red mat called barimemea or simply bari which

is barimaita dyed red. Bwana or big red mat is a kind of traditional money and

plays an important role in the life of North Raga. Bari or a small red mat is

used for a supplement of big red mat in the case of exchange or payment.

Small red mat is also used as a traditional dress. Women used it as a loincloth and

men as a G-string.

Pigs are classified into three kinds, that is, sows (dura), bisexual pigs

(ravwe), and boars. There is no special Raga name for a boar and it is usually

called boe which is the general name for a pig. Both of bisexual pigs and boars

have tusks but now we can not find bisexual pigs in North Raga. Boars are

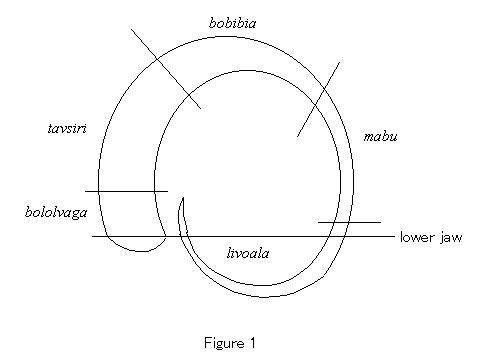

classified according to the size of the tusk (Figure 1). Boars which do not have

tusks yet are called udurugu. Boars whose tusks are just coming out from the lower

jaw are called bololvaga. You can know that it has small tusks only when it opens

its mouth. When its tusks come out of the mouth piercing the upper lip, the pig is

called tavsiri. Boars whose tusks are curving and reach cheeks are called bobibia.

Boars which have rounded tusks are called mabu, the meaning of which is to rest. It

is called mabu because the tips of the tusk comes back to the bone of the lower jaw

and stops there. Boars whose tusks are growing more and start to draw second arc

are called livoala.

Ⅱ

(1) First stage in the village of the bridegroom

On a day before marriage, people come together to the village of the

bridegroom. They are atatun mwalanggelo. Today, a kind of bwalaitoa (joking

behavior) is occasionally held. Snake has an important role in this joking

behavior. The classificatory mothers of the bridegroom dance savagoro

dance in the meeting house (gamali) while outside the meeting house, the

father's sisters of the bridegroom dance tigo dance with long bamboos in

their hands in which snakes are packed. Then the latter group goes into the

meeting house and they strike the bamboo on the floor of the meeting house in

order that the snakes may come out. A great uproar occurs. They grasp the

snake and tear off. The father's sisters block the door of the meeting house

with flames of palm torches in order that the classificatory mothers can not

go outside. After that, the father's sister goes out of the meeting

house with a piece of snake in her hand. She is given a big red mat in the

form of hunhuni. This is said to have been the original custom of the Central and

was introduced to the North recently.(5)

After this kind of bwalaitoa, comes hunhuni in which the bridegroom puts the end

of an unfolded big red mat over his head and gives it to his classificatory father

or father's sister who worked for the preparation of the banquet of the following

day or will do some kind of work in it. The men who were requested to

fetch firewood, stones for the earth-oven, leaves for cooking, and kava plant from

the field are all given big red mats in hunhuni. The man of B village in the

above example who is requested to fetch firewood is given a big red mat in

this manner.(6) The men who are requested to make kava beverage, carry buckets of

water for kava making, peal taros or yams, kill a cattle in order to prepare side

dishes in the banquet of the following day, and to do savagoro dance after following

day's ceremony are also given big red mats in this scene.

As was mentioned above, a man who is requested to fetch firewood cuts

them down from the field of the land of a person of the same village as him.

As for the leaves for cooking, the real father of the bridegroom usually says,

“You take them from my field or my son's field”. In spite of such a

suggestion, the man, who was asked for the work, often takes them from his own

field since these leaves grow quickly and are not so valuable. But kava is usually

cut down from the field of the real father of the bridegroom. As for stones for

the earth-oven, every place is accessible for this task.

There are some differences between hunhuni to the fathers and that to the

father's sisters. In the former case, a big red mat is given to each man while in

the latter case some small red mats are added to a big red mat. Such small red

mats are usually given to the father's sister of the bridegroom with no expectation

of returning gift. This kind of gift is called tabeana. In the case that several

small mats are given to the father's sister, these mats are sometimes regarded as

vuro, which means a debt. This is often informed to the mat-receiver orally. If a

mat is given as vuro, a mat of the same value should be given back in future to the

mat-giver who is basically the real parents of the bridegroom (the return gift is

called sobwesobwe).(7)

In this way, many mats are necessary for the real parents of the bridegroom,

to whom many mats have been given in advance by their relatives. On the day of

hunhuni, the father's sisters as well as the classificatory mothers and sisters of

the bridegroom come to his village with a lot of mats. The mats of the former are

given to his real parents as vuro which should be given back in the future to the

father's sisters, while those of the latter are given as tabeana which means that

there is no obligation to do a return gift to them.

The big red mat transacted in hunhuni is regarded as mwemwearuvwa.

Mwemwearuvwa is an intermediary category between tabeana and vuro in the sense that

a return gift is not needed with tabeana and it is a must with vuro while it is

“expected”with mwemwearuvwa. In the other words, although a mat-giver is not

able to demand a return gift to the mat-receiver, the latter is expected to do it

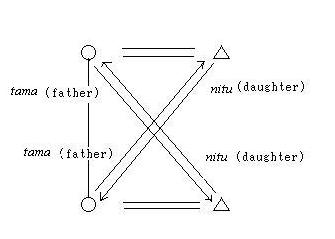

in the fixed manner. Suppose a classificatory father A is requested to fetch

firewood and is given a big red mat in hunhuni from the real father B of the

bridegroom D. A is expected to give back a big red mat to B in the case of the

marriage ceremony of A's son C in which A asks B for cutting firewood or the

other work and puts a big red mat over the head of C and gives it to B (Figure 2).

(2) First stage in the village of the bride.

In the village of the bride, things which the bride brings with her on

the day of the marriage are prepared. They consist of two big sacks woven of

pandanus leaves called tangbunia and daily commodities such as an alcohol lamp, a

bush knife, a suit case, dishes, seats, cups, dresses and so on.

Sacks are filled with mats. One of the two sacks is filled with one big

white mat, many big red mats, and many small red mats. These are basically

prepared by the bride's real mother and real father and are to be owned by

the bride. This action is called hohogonivwa and the day is also named

hohogonivwa of so-and-so (the name of the bride). The other sack was filled,

as was observed in a marriage ceremony by me in 1981, with one big white mat and

six big red mats. These are prepared by the bride's fathers and are put in

the sack by her father's sisters. Her real father prepares two red mats,

one classificatory father prepares one white mat as well as one red mat, and

three classificatory fathers prepare one red mat respectively. These five

fathers of the bride including her real father play important roles in the

marriage ceremony as well as her marriage life. I refer to them here as the

bride's FATHERS.

FATHERS are the receiver of the bride wealth, which consists of pigs.

The information about the number and status of pigs is announced in advance

to the people of the bride's side. FATHERS, considering how many mats are

equal to what status of pig, put their own mats in the sack. In this

marriage case, the bride wealth consists of five pigs, that is, bobibia,

tavsiri, 2 bololvagas, and udurugu. Real father of the bride who puts two big red

mats in the sack will get bobibia, the classificatory father who presents a

big white mat and a big red mat will get tavsiri, and each of other three

classificatory fathers who give a big red mat will get the remaining pigs

respectively. Six red mats the FATHERS of the bride put in the sack will

go to the bridegroom although the white mat will be owned by the bride.

Some of the daily commodities and money are given to the bride by her

kin. The bride's kin in this context means the members of her moiety and her

tamas (fathers) and vwavwas (father's sisters) who are in the other moiety.

The moiety members who are her tarabe (mother's brothers), her tua (sisters), or

her hogosi (brothers) mainly give money to the bride. Such a present is called

tabeana but some men think such a gift is a kind of mwemwearuvwa. The

bride's classificatory fathers who give her an alcohol lamp, a bush knife, or

a suit case are different persons from her FATHERS mentioned above. Those things

given by them or the bride's father's sisters should be reciprocated by big

red mats in the scene of hunhuni which is held later on the same day.

In hunhuni many classificatory fathers or father's sisters of the bride

besides those mentioned above are given big red mats. Although the big

banquet will be held in the village of the bridegroom the following day, today's

banquet in the village of the bride should be arranged by the real father of

the bride. Classificatory fathers who are asked to cut down firewood, or the

other works are also given big red mats here. The classificatory fathers or

father's sisters who previously gave big red mats as vuro to the parents of the

bride will take sobwesowbe (return gift) in this hunhuni. Persons who always give

assistance to the bride or FATHERS and their wives may also become the mat-

receiver here, while the mat-giver is basically limited to the FATHERS and

their wives.

Ⅲ

(1) Second stage

On the day of the marriage ceremony, first of all, the bride with

things such as big sacks and commodities is taken over to the people of

the bridegroom's side. In the house of the bride, people of the bride's side

are seen to cry. Then the mothers, sisters, and father's sisters of the bridegroom

go with making a big noise. This is a kind of bwalaitoa, that is, a joking behavior.

In this scene, the father's sisters pour muddy water on the mothers and sisters or

the former tickles the latter. After that, the bride led by

one of her father's sisters goes out of her house. They put an unfolded big

red mat over their heads so that the bride may not visible clearly.

In some marriages, hunhuni is held near her house. Although in

olden days,the bride killed a tusked boar at this time, now she only taps

the head or skull of the tusked pig by a walking stick. This was and is one

of occasions for a woman to get a pig-name.

There is a graded system for woman in North Raga.(8) Women enter the

graded system by killing pigs of prescribed status and number. See figure 3.