THE STORY OF RAGA: A MAN'S ETHNOGRAPHY ON

HIS OWN SOCIETY (Ⅲ)MARRIAGE

Masanori

YOSHIOKA

INTRODUCTION

This is the third part of an English

translation of a hand-copied book

which was written in the “Raga”language

by the late Rev. David Tevimule in

1966. “Raga”is a language spoken by the

people of North Raga (northern part

of Raga or Pentecost Island) in Vanuatu.

The work consists of twenty chapters,

which cover various aspects of North Raga

culture: its origin myth, kin

relations, graded system, chiefs, initiation

rite and customs ranging from

birth, marriage, to death. In this paper

I translate Chapters 8 and 9 in

which Rev. David Tevimule describes customs

concerning marriage.(1) Although

he starts his description from the birth

of a girl and refers to the custom

of so-called infant betrothal, his main

concern is on the marriage ceremony.

Ⅰ

Here I present some materials concerning

marriage ceremony which were

collected during my field researches. Marriage

ceremony is classified into

two kinds, one of which is called kastom marit (custom marriage) in Bislama

(Vanuatu pidgin) and the other of which is

jos marit (church marriage). Kastom

marit is usually referred to as lagiana in

Raga language and is thought to be

based on halan lagiana (the road of the marriage) which has been

practiced from

before. I will describe this kind of marriage

ceremony, which I tentatively

call traditional. It is equal in major points

to the ceremony which is

described by Rev. Tevimule but is different

in some minor points.

A traditional marriage ceremony is

composed of three stages. The first stage

is held on the day before marriage in the

village of the bride and the bridegroom

respectively. This is the pre-stage of the

marriage ceremony. In each side

they prepare for the day of marriage. The

second stage is held in the village

of the bride on the day of marriage. At this

stage, people of the bridegroom's side

take the bride and her belongings to the

village of the bridegroom. After the

second stage, all the attendants move to

the village of the bridegroom, where the

third stage is held. Here the bride wealth

is bestowed to the bridegroom.(2)

In this way, the people of the bride's

side as well as those of the

bridegroom's side lastly come together to

the village of the bridegroom, where

the big banquet is given. The people of the

bride which is called atatun vavine

(the side of the woman) are composed of the

tama (father) of the bride, her

vwavwa (father's sister), the bride's cluster members,

and her moiety members other

than the bridegroom's tama and vwavwa.(3) The same classification is also applied

to the people of the bridegroom (atatun mwalanggelo:the side of the young boy). Those

people are entertained with a lot of kava

and meals cooked in the earth-oven in the

banquet, which is managed by the real father

of the bridegroom.

Kava is a beverage prepared from the

roots of the plant with the same

name (Piper methysticum). Kava is usually planted in the field far

away from the

village. It is not an easy work to bring

a lot of kava roots from the field

to the village. This is, however, just an

initial step to produce a kava drink.

There remains the process to prepare a beverage

from its roots. First, kava

roots are cut into small pieces. Then you

pick a handful of these pieces with the

left hand and a serrated stone with the right

hand. The kava pieces are thus

grounded and twisted by both hands. A little

water is added to the smashed kava

roots and they are kneaded. Some amount of

liquid comes out from squeezing these

kneaded roots. It is not drinkable yet. It

becomes drinkable when it is

filtered by a sheet of coconut fiber and

is served in a coconut cup.(4)

The food in the earth-oven is called

vwavwaligi. When vwavwaligi is

made, first of all, you have to have many

stones burned by firewood in the

earth-oven. After the stones are well heated,

they are removed from the oven. Then

leaves of heliconia (Heliconia indica) are

laid on the heated bottom of the earth-

oven, and raw foods wrapped up in the same

leaves are put on them. After the oven

is filled with foods, they are covered again

with these leaves. Finally, the heated

stones, which have been removed from the

oven in the prior step are put on these

leaves (Photo 1). When the stones cool down

after several hours, the cooking is

finished. Vwavwaligi is a kind of baking in a casserole. In this

way, vwavwaligi

requires many stones to be burned, a lot

of pieces of firewood which burn stones,

and leaves of heliconia by which the ingredients

are wrapped. The classificatory

fathers and father's sisters of the bridegroom

are asked to fetch firewood from

the field, to bring stones to be burned from

the stone ground one can find such

kind of stones, to bring leaves from the

field, and so on.

Here is an example to illustrate this

procedure. Suppose that the marriage

ceremony is held at A village and a man of

B village (who is a classificatory

father of the bridegroom) is requested to

fetch firewood for earth-oven. The date

of the works is fixed by the real father

of the bridegroom. On the day, this man

sets to work with the assistance of the people

of B village. The firewood is cut

down from the field owned by the people of

B village. The field which has a lot of

pieces of firewood and is near A village

is selected. They start to work in the

morning. The lunch is served in A village.

Since the other works such as collecting

leaves, bringing stones, and so on are also

done on the same day, a lot of people

who come from several villages in North Raga

eat lunch in A village. After lunch,

they work again till evening when they go

back to A village. In the village, kava

and supper are prepared by the people of

A village. People who finished working are

served to drink kava. After drinking kava,

each of them is given a basket filled

with meals (taro or yam and meats etc.) for

supper and they go back to their own

village with these baskets.

Through the marriage ceremony, there

are two kinds of North Ragan wealth,

which play important roles, that is, big

red mat and pig. There are four kinds of

mat in North Raga. One is a big white mat

called bwanmaita which is woven of

pandunus leaves. Another is a big red mat

called bwanmemea which is the

bwanmaita dyed red. Bwanmemea is often referred to as simply bwana. Another

mat is a small white mat called barimaita which is also woven of pandanus

leaves. The other mat is a small red mat

called barimemea or simply bari which

is barimaita dyed red. Bwana or big red mat is a kind of traditional

money and

plays an important role in the life of North

Raga. Bari or a small red mat is

used for a supplement of big red mat in the

case of exchange or payment.

Small red mat is also used as a traditional

dress. Women used it as a loincloth and

men as a G-string.

Pigs are classified into three kinds,

that is, sows (dura), bisexual pigs

(ravwe), and boars. There is no special Raga name

for a boar and it is usually

called boe which is the general name for a pig. Both

of bisexual pigs and boars

have tusks but now we can not find bisexual

pigs in North Raga. Boars are

classified according to the size of the tusk

(Figure 1). Boars which do not have

tusks yet are called udurugu. Boars whose tusks are just coming out from

the lower

jaw are called bololvaga. You can know that it has small tusks only

when it opens

its mouth. When its tusks come out of the

mouth piercing the upper lip, the pig is

called tavsiri. Boars whose tusks are curving and reach

cheeks are called bobibia.

Boars which have rounded tusks are called

mabu, the meaning of which is to rest. It

is called mabu because the tips of the tusk comes back to

the bone of the lower jaw

and stops there. Boars whose tusks are growing

more and start to draw second arc

are called livoala.

Ⅱ

(1) First stage in the village of the bridegroom

On a day before marriage, people come

together to the village of the

bridegroom. They are atatun mwalanggelo. Today, a kind of bwalaitoa (joking

behavior) is occasionally held. Snake has

an important role in this joking

behavior. The classificatory mothers of the

bridegroom dance savagoro

dance in the meeting house (gamali) while outside the meeting house, the

father's sisters of the bridegroom dance tigo dance with long bamboos in

their hands in which snakes are packed. Then

the latter group goes into the

meeting house and they strike the bamboo

on the floor of the meeting house in

order that the snakes may come out. A great

uproar occurs. They grasp the

snake and tear off. The father's sisters

block the door of the meeting house

with flames of palm torches in order that

the classificatory mothers can not

go outside (Photo 2). After that, the father's

sister goes out of the meeting

house with a piece of snake in her hand.

She is given a big red mat in the

form of hunhuni. This is said to have been

the original custom of the Central and

was introduced to the North recently.(5)

After this kind of bwalaitoa, comes hunhuni in which the bridegroom puts the end

of an unfolded big red mat over his head

and gives it to his classificatory father

or father's sister who worked for the preparation

of the banquet of the following

day or will do some kind of work in it (see

Photo 3). The men who were requested to

fetch firewood, stones for the earth-oven,

leaves for cooking, and kava plant from

the field are all given big red mats in hunhuni. The man of B village in the

above example who is requested to fetch firewood

is given a big red mat in

this manner.(6) The men who are requested

to make kava beverage, carry buckets of

water for kava making, peal taros or yams,

kill a cattle in order to prepare side

dishes in the banquet of the following day,

and to do savagoro dance after following

day's ceremony are also given big red mats

in this scene.

As was mentioned above, a man who is

requested to fetch firewood cuts

them down from the field of the land of a

person of the same village as him.

As for the leaves for cooking, the real father

of the bridegroom usually says,

“You take them from my field or my son's

field”. In spite of such a

suggestion, the man, who was asked for the

work, often takes them from his own

field since these leaves grow quickly and

are not so valuable. But kava is usually

cut down from the field of the real father

of the bridegroom. As for stones for

the earth-oven, every place is accessible

for this task.

There are some differences between

hunhuni to the fathers and that to the

father's sisters. In the former case, a big

red mat is given to each man while in

the latter case some small red mats are added

to a big red mat. Such small red

mats are usually given to the father's sister

of the bridegroom with no expectation

of returning gift. This kind of gift is called tabeana. In the case that several

small mats are given to the father's sister,

these mats are sometimes regarded as

vuro, which means a debt. This is often informed

to the mat-receiver orally. If a

mat is given as vuro, a mat of the same value should be given

back in future to the

mat-giver who is basically the real parents

of the bridegroom (the return gift is

called sobwesobwe).(7)

In this way, many mats are necessary

for the real parents of the bridegroom,

to whom many mats have been given in advance

by their relatives. On the day of

hunhuni, the father's sisters as well as the classificatory

mothers and sisters of

the bridegroom come to his village with a

lot of mats. The mats of the former are

given to his real parents as vuro which should be given back in the future

to the

father's sisters, while those of the latter

are given as tabeana which means that

there is no obligation to do a return gift

to them.

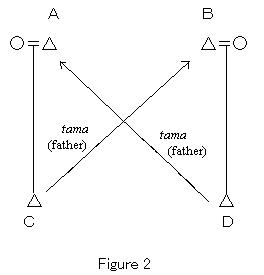

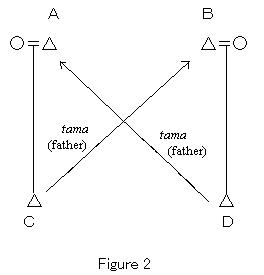

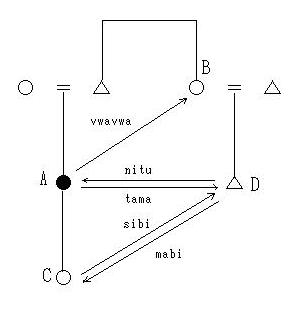

The big red mat transacted in hunhuni

is regarded as mwemwearuvwa.

Mwemwearuvwa is an intermediary category between tabeana and vuro in the sense that

a return gift is not needed with tabeana and it is a must with vuro while it is

“expected”with mwemwearuvwa. In the other words, although a mat-giver

is not

able to demand a return gift to the mat-receiver,

the latter is expected to do it

in the fixed manner. Suppose a classificatory

father A is requested to fetch

firewood and is given a big red mat in hunhuni from the real father B of the

bridegroom D. A is expected to give back

a big red mat to B in the case of the

marriage ceremony of A's son C in which A

asks B for cutting firewood or the

other work and puts a big red mat over the

head of C and gives it to B (Figure 2).

(2) First stage in the village of the bride.

In the village of the bride, things

which the bride brings with her on

the day of the marriage are prepared. They

consist of two big sacks woven of

pandanus leaves called tangbunia and daily commodities such as an alcohol

lamp, a

bush knife, a suit case, dishes, seats, cups,

dresses and so on.

Sacks are filled with mats. One of

the two sacks is filled with one big

white mat, many big red mats, and many small

red mats. These are basically

prepared by the bride's real mother and real

father and are to be owned by

the bride. This action is called hohogonivwa and the day is also named

hohogonivwa of so-and-so (the name of the bride). The

other sack was filled,

as was observed in a marriage ceremony by

me in 1981, with one big white mat and

six big red mats. These are prepared by the

bride's fathers and are put in

the sack by her father's sisters. Her real

father prepares two red mats,

one classificatory father prepares one white

mat as well as one red mat, and

three classificatory fathers prepare one

red mat respectively. These five

fathers of the bride including her real father

play important roles in the

marriage ceremony as well as her marriage

life. I refer to them here as the

bride's FATHERS.

FATHERS are the receiver of the bride

wealth, which consists of pigs.

The information about the number and status

of pigs is announced in advance

to the people of the bride's side. FATHERS,

considering how many mats are

equal to what status of pig, put their own

mats in the sack. In this

marriage case, the bride wealth consists

of five pigs, that is, bobibia,

tavsiri, 2 bololvagas, and udurugu. Real father of the bride who puts two big

red

mats in the sack will get bobibia, the classificatory father who presents

a

big white mat and a big red mat will get tavsiri, and each of other three

classificatory fathers who give a big red

mat will get the remaining pigs

respectively. Six red mats the FATHERS of

the bride put in the sack will

go to the bridegroom although the white mat

will be owned by the bride.

Some of the daily commodities and money are

given to the bride by her

kin. The bride's kin in this context means

the members of her moiety and her

tamas (fathers) and vwavwas (father's sisters) who are in the other

moiety.

The moiety members who are her tarabe (mother's brothers), her tua (sisters), or

her hogosi (brothers) mainly give money to the bride.

Such a present is called

tabeana but some men think such a gift is a kind

of mwemwearuvwa. The

bride's classificatory fathers who give her

an alcohol lamp, a bush knife, or

a suit case are different persons from her

FATHERS mentioned above. Those things

given by them or the bride's father's sisters

should be reciprocated by big

red mats in the scene of hunhuni which is held later on the same day.

In hunhuni many classificatory fathers or father's

sisters of the bride

besides those mentioned above are given big

red mats. Although the big

banquet will be held in the village of the

bridegroom the following day, today's

banquet in the village of the bride should

be arranged by the real father of

the bride. Classificatory fathers who are

asked to cut down firewood, or the

other works are also given big red mats here.

The classificatory fathers or

father's sisters who previously gave big

red mats as vuro to the parents of the

bride will take sobwesowbe (return gift) in this hunhuni. Persons who always give

assistance to the bride or FATHERS and their

wives may also become the mat-

receiver here, while the mat-giver is basically

limited to the FATHERS and

their wives.

Ⅲ

(1) Second stage

On the day of the marriage ceremony,

first of all, the bride with

things such as big sacks and commodities

is taken over to the people of

the bridegroom's side. In the house of the

bride, people of the bride's side

are seen to cry. Then the mothers, sisters,

and father's sisters of the bridegroom

go with making a big noise. This is a kind

of bwalaitoa, that is, a joking behavior.

In this scene, the father's sisters pour

muddy water on the mothers and sisters or

the former tickles the latter (see Photo

4). After that, the bride led by

one of her father's sisters goes out of her

house. They put an unfolded big

red mat over their heads so that the bride

may not visible clearly

In some marriages, hunhuni is held near her house. Although in

olden days,the bride killed a tusked boar

at this time, now she only taps

the head or skull of the tusked pig by a

walking stick. This was and is one

of occasions for a woman to get a pig-name.

There is a graded system for woman

in North Raga.(8) Women enter the

graded system by killing pigs of prescribed

status and number. See figure 3.

| Name of the grade |

Pig to be killed |

| status |

number |

mwei

mitari

mwisale

mitalai

motari

|

udurugu

bololvaga

tavsiri

bobibia

mabu or livoala

|

1

1

1

1

1

|

Figure 3

When she kills a tusked boar to enter a new

grade, she gets a new name after

the name of the grade. This is the pig-name

(iha boe). For example,a woman of

the lowest grade mwei may be named Mweimaiana while a woman of motari, the

highest grade, may be named Motariala. As mentioned above, nowaday the bride

does not really kill a pig but usually tap

the head of the pig by a walking

stick. However this is enough to get a new

pig-name.

After such a scene, the bride led by

her father's sister moves to the

middle of the ceremonial ground (sara) in the village. The bride's things such

as two big sacks and commodities which are

brought to the village of the

bridegroom are put there and the bride with

her father's sister who is

covered with an unfolded big red mat and

the real father of the bride stand

by these things. The people of the bridegroom

are gathering in the end of

the ceremonial ground and make hunhuni in which some of the classificatory

fathers and father's sisters of the bridegroom

are given big red mats. These

persons will play a role of taking the bride

as well as the bride's things.

After hunhuni, they walk over to those people standing

in the middle of the

ceremonial ground, circulate them, and touch

the hem of the clothes of the

real father of the bride in turn. This means

that they receive the bride and

the bride's things from him(see Photo 6).

A raw yam is put on one sack in which

mats were packed by FATHERS.

One of the mothers of the bridegroom brings

this sack while the other

sack is carried by one of the mothers of

the bride. One of the sisters of

the bridegroom (not necessarily his real

sister) gnaws a bit of the raw yam

and spits it out. This is said to mean that

her brother (the bridegroom)

“spits out” his semen to the bride. This

yam is cooked and eaten only by

the sisters of the bridegroom. Then, all

of the attendants move to the

village of the bridegroom. On the way to

the village of the bridegroom, a

kind of bwalaitoa was held before but is not held in recent

marriage

ceremonies. I observed only one case in 1974

in which a man hit persons with

island broom.(9)

(2) Third stage

In the village of the bridegroom, the

bride wealth is given to the

FATHERS of the bride. Prior to the opening

of the ceremony, many posts have

been set on the ceremonial ground in two

lines. One line is called gain boe

(post of pig) and the other is called gain lingilingiana (post of lingilingiana).

Pigs fastened to the posts in the former

line are the bride wealth (volin

vavine = the payment of the woman) and they go

to the FATHERS of the bride.

The bride wealth is sometimes prepared

only by the bridegroom and

sometimes by his relatives. When his real

father presents pigs as the bride

wealth, these pigs are regarded as tabeana to him. In this case, the mats the

FATHERS of the bride put in the sack are

all owned by the bridegroom. When

the other relatives of the bridegroom such

as his classificatory father, his

brother, his sister's son or any relative

present pigs as the bride wealth,

these pigs are regarded to be compensated.

Usually these gifts are

compensated by the mats of the FATHERS of

the bride. For example, in the case

that the bridegroom presents his own bobibia and bololvaga, his real father

tavsiri and udurugu, and his classificatory father bololvaga and six big red

mats were put in the sack by the FATHERS

of the bride, five mats will be

owned by the bridegroom and one by his classificatory

father.

On the ceremonial ground, big red mats

the number of which is the same

as that of pigs are put besides them. These

mats which are called raun longgo

(leaf of laplap: laplap is a kind of pudding)

go to the father's sisters of the bride.

The pigs fastened to the posts in the latter

line are used in lingilingiana which is

the scene of the exchange of pigs and big

red mats.

Two more posts are built on the ground

between these two lines of posts.

A note of 1000 vatu is attached to one of

these two posts.(10) This is

called tavwen bibiliana (the payment for the dirty works) which

is given to

the real mother or parents of the bride from

the parents of the bridegroom.

This is said to be the payment for the personal

needs of the bride as a baby.

To the other post of these two is fastened

a sow called duran vavine (a sow

of the woman), which is given to the real

mother of the bride from the

parents of the bridegroom.

Now the bridegroom gives a big red

mat to his classificatory father who

is also chief (ratahigi) in the hunhuni manner.(11) Then the bridegroom stands

by the posts to which many pigs are fastened.

The chief mentioned above

gives the bridegroom advices about life in

a big voice (see Photo 7). After

that, the FATHERS of the bride and their

wives walk to the bridegroom on the

ceremonial ground, circle around him and

all of the pigs, and touch the

hem of his clothes respectively. They bring

all of the pigs and big red mats.

This is the scene in which the bride wealth

is given to the father of the

bride. Pigs as bride wealth are those fastened

to the posts in one line, the

number of which is usually five. The other

many pigs are the object of the

exchange in lingilingiana.

In lingilingiana, each of the mother of the bride puts some

big red mats

over the head of the bride and says to the

bridegroom, for example,“ Father,

your three big red mats and ten small red

mats are there( Bwanamwa,tata,

gaitolu mai malomwa hangvulu).”(12) The mother of the bride refers to

the

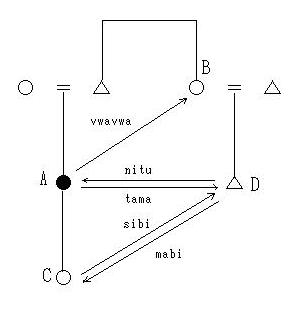

bridegroom as father because she is his daughter(nitu)(Figure 4).(13) Then

the bridegroom comes to the bride to take

these mats.

Figure 4

Those women prepare these mats assuming

that these mats may have

equal value to so and so status of pig. The

exchange of mats and pigs in

linglingiana is roughly based on the equivalence rule

shown in Figure 5. In

one marriage ceremony, twenty three persons

presented mats in lingilingiana.

| status of pig |

mats |

udurugu

bololvaga

tavsiri

bobibia

mabu

livoala

|

1 big red mat

2 big red mats and 5 or 10 small red mat

3 big red mats and 10 small red mats

4 big red mats and 10 small red mats

5 big red mats and 10 small red mats

6 big red mats and 10 small red mats

|

Figure 5

The number of persons who present mats

is sometimes over that of pigs. In

this case, some persons who can not find

pigs to be exchanged with mats go

back home with their mats. Sometimes the

owner of the pig does not agree

that the presented mats have equal value

to his pig. In this case, the

exchange is not settled. In certain marriage

ceremony, although a woman

presented three big red mats and ten small

red mats in order to get tavsiri,

there remained no tavsiri. Then the woman lastly decided to exchange

two big

red mats and ten small red mats with bololvaga. In an another marriage

ceremony, a woman presented four big red

mats and forty small red mats to

get livoala. The exchange was successfully transacted

in this case.

After lingilingiana, the bride goes to the house of the bridegroom.

One

of his sisters puts a green leaf of coconut

on the floor as the sitting

place of the bride. She is given a small

red mat for this action. The real

father of the bride said, “This is your

sitting place, my daughter, forever

forever (Tanomwa hangge geki mwei vai tuai vai tuai).” Then begins bwanlailai.

Here the real mother of the bride gives big

red mats to the sisters or

brothers of the bridegroom who assisted meals,

kava, mats in the marriage

ceremony.

While bwanlailai is performed in front

of the house of the bridegroom,

three earth-ovens are set in the meeting

house, where vwavwaligi is made. In

the first oven named “the oven for all,”

tubercles such as taros or yams

and the meats of the beasts such as pigs

which were killed for the today's

banquet or recently cattle are cooked. These

meals are for all of the

attendants to the ceremony. The meals cooked

in the second oven named “the

oven for the father of the bride”are only

for the fathers and the father's

sisters of the bride. The third oven named

“the oven for the mother of the

bride” supplies the meals for the maternal

kin of the bride such as the

bride's mothers, mother's brothers, brothers,

sisters, and children etc. The

meals cooked in the third oven is specially

called umu which contains

cooked sow. The sow cooked in this oven is

usually presented by the parent

of the bridegroom, sometimes by his mother's

brother. A big red mat called

specially bwanan umu (a big red mat of umu) as well as five or ten small

red mats are given to the person who presents

the sow by the mother of the

bride. I observed in a certain marriage ceremony

that the real mother of the

bride presented a big red mat and a classificatory

mother ten small red mats.

Before taking umu from the oven, one of the classificatory

mothers of

the bride treads on stones which were put

on leaves of heliconia covering

umu. This means that a child of this woman will

marry in the near future.

In the case of the marriage ceremony above

mentioned, a woman who presented

ten small red mats for umu treaded on the

stones.

In olden days, after the marriage ceremony,

the attendants went back to

their own village except the FATHERS of the

bride and their wives, who

slept in the village of the bridegroom. The

following day, they went back

home with tanmosi, which was a special vwavwaligi made by the bridegroom all

night. He killed a fowl for each couple and

cooked it in vwavwaligi. Now

many people of the bride's side sleep in

the village of the bridegroom. Next

day, all of them go home with meals in baskets

which are also called tanmosi.

Notes to Introduction

(1) I already translated Chapters 1 to 5

into English in “The Story of Raga

I”(Yoshioka 1987), and Chapters 6 to

7 in “The Story of Raga II”

(Yoshioka 1988). As for the vocabulary

of Raga language, see Yoshioka

and Leona 1992. I am grateful to my colleague

Masayuki Kato for his

helpful comments on an earlier version of

this paper.

(2) After such a traditional marriage ceremony

(or in some cases before the

ceremony) young couple has a church marriage.

Now most people of North

Raga are Christian. I observed the traditional

marriage ceremony nine

times during my field researches in 1974,

1981-1982, 1985, 1991, 1992,

1996, and in 1997. Here I describe the traditional

marriage ceremony

mainly based on the observation of that which

was held on 25th in

September in 1981. It is supplemented by

the data of other marriage

ceremonies which are basically similar to

that of 1981 in spite of the

gap of time.

(3) North Raga has matrilineal moieties which

are themselves divided into

four groups which I named cluster. As for

the kin terms, see Yoshioka

1988.

(4) This is how to make kava beverage in

North Raga. In the southern islands

in Vanuatu, kava roots are chewed instead

of being smashed by a stone.

(5) The meeting house (gamali) has been described in the anthropological

documents as the men's house. It is called

men's house because women

have been said to be prohibited to enter

into it. In North Raga, however,

a special woman who finished certain rituals

has been traditionally

allowed to enter into it. See Yoshioka 1994.

(6) However the people of his village who

assisted him are given nothing.

For them, the lunch, the supper, and kava

are tavwe (payment) for their

works. But the taros or yams which are cooked

for lunch or supper

are given to the people of B village from

those of A village in advance.

In this way, the payment for the work (tavwe) in this case is consisted

mainly of the work for cooking.

(7) A big red mat (bwana) given as vuro is often called bwanmosi while a

small red mat (bari) given as vuro, barimosi. The return gift for bwanmosi

is often called bwanvwalvwaliu, while that for barimosi, barivwalivwaliu.

(8) The graded system for men will be discussed

in “The Story of Raga V.”

See Yoshioka 1998.

(9) In this case, a hitting man might be tama (father) of the bridegroom while

hit persons were those of the side of the

bridegroom such as his ratahi

(mother), his tarabe (mother's brother), his tua (brothers), and his hogosi

(sisters) etc.

(10)Vatu is a currency of Vanuatu.

(11)Ratahigi is a traditional political leader who is

in the highest grade

vira in the graded system of North Raga.

Ratahigi is translated as jif

(chief) in Bislama.

(12)A small red mat is called malo (G-string) when it is given to men.

(13)Today, not only the mother of the bride

but also her mother's brothers

participate in lingilingiana as mat-giver.

They also call the bridegroom

their father.

References

Yoshioka, M

1987 “The Story of Raga:A Man's Ethnography

on his Own Society (I) The

Origin Myth.”Shinshudaigaku

Kyoyobu Kiyo 21:1-66 (Faculty of Liberal

Arts, Shinshu University)

1988 “The Story of Raga:A Man's Ethnography

on his Own Society (II) Kin

Relations.”Shinshudaigaku Kyoyobu

Kiyo 22:19-46 (Faculty of Liberal

Arts, Shinshu University)

1994 “Taboo and Tabooed:Women in North

Raga of Vanuatu.”K.Yamaji (ed.)

Gender and Fertility in Melanesia.

Dept. of Anthropology, Kwansei Gakuin

University. pp.75-108

1998 Meranesia no Ikai Kaiteisei Shakai:Hokubu

Raga ni okeru Shinzoku, Koukan,

Ridashippu (The Graded System

in Melanesia: Kinship, Exchange and

Leadership in North Raga) in

Japanese, Tokyo:Fukyosha.

Yoshioka,M and R.Leona

1992 “A Vocabulary of the North Raga

Language: Olgeta Tok long Lanwis

blong Not Pentekost.”Kindai

72:1-39. (Faculty of Cross Cultural

Studies, Kobe University)

VEVHURIN RAGA

Tavaluna 8

1)Be dura nu vahuhu atamani i vavine, sa

mwata nu vahuhu nituna atamani i

vavine. Kera geki ran lagi ram bav ira

nitura. Ram ivusi mai nitun houn

talai i matmaita. Ta naturi vavine kea gaiviha,

naturi atamani hen ivusi.

(1) Ira lagi gairua raru bav nitura mwalanggelo

ramuru gita vavine vwate

nu ros atatu. Ramuru lai nitu boe sa bwana,

ramuru lai nitura mwalanggelo

men tai man simango. I kea mwa dai simango

gin boe sa bwana(2) mwa en gi

vuron vavine. Niu mwa hav vora te niu mwasigi

ta ihana be binihi marahi,

be naturigi vi vora ta bwativun non ginau

boe sa bwana kea. Vavine ros

atatu havan mwalanggelo.(3) Nu hanggo nituna.

2)Naturigi atamani, ira gitanggoro ram uloi

wangga be U U. Be naturi vavine,

gitanggoro ram bev gin silo gaivua be imwa

duluai rav rongoe be tasalana

ata Ute taragaiana.(5) Ira hei ram iloe be

vavine. Ram lai bari, naturigi

nu hunia(6) lalai bilan vwavwa gonggonai,

bwatuna be binihi marahi.

Mwahavana vavine mwa hanggo atatu, aloan

tamana abena atamani. Hogisin

tamana vi lai damu vi wehi toa vi valinia

vi vugea vi laia gi gan vavine,

gabe nituna nu vora ta vavine, vwavwa bilan

vavine hanggo atatu nituna

atamani. Atatu duluai ram iloe be naturi

vavine kea aloan tamana nu van

nggoroe huba, raru vi lagi vai nongoiha.(7)

Tuhuba vavine hanggo atatu vi

eno gubweng hangvulu vi garuhi bibilin voroana.

Naturi vavine mwa

daulatoga tauluna 10 sa hanvul doma, ratahin

daulato vi hingge bilan

vwavwa vi vugeri(8) bwanana, gabe nu lai

mahalei nggoro daulato.(9) Take

mwalanggelo i daulato ramuru hav lagi te

radu. Be daulato nu ilo bwana non

ratahina take vi matagu vi lalagi(10) radu.

3)Taman mwalanggelo i ratahina raru vi gita

boe gaitolu sa gailima, muan boe

livona nu en lol iluna sa bobibia, bwanmemea

gailima sa hangvulu. Nitura

men lagi. Kunia mulei tabwalugu(11) vi lihilihi.(12)

Vi lai bwanmemea

lalai bilan vwavwa sa havana vwate vavine

lavoa i non lavoa non vavine vi

lol non lihilihi. Kea vi lihi ginau hangvulu

doma sa 20. Be nitun ratahigi,

(13) liu 50. Tamana vwate vi lai boe, boe

livo kea vi wehia vi lol

ginaganiana. Be tabwalugu nitun ratahigi

vi wehi boe mabu sa livoala.(14)

Bongi ira vavine rav lol singisingi rav tigo

vi rani. Ira bilan vwavwa rav

lai tabwalugu be vi gagaru an tahi. Rav hamai

nin tahi i gem wehi boe ba

hae lol gamali(15) i gem lihi ginau duluai

matbongon gamali. Keki huri

nitun ratahigi ngano.

4)Nitun atatu hivhivo ram lol lalanggovanana

ngan la imwan tamana vi lihi ①

sori ② bari sa bari gairua ③ uli ④ lalau

⑤ bunbune sa bunbune gairua

sa gaitolu ⑥ livon boe vi tagarae sa livo

gairua be nu wehi boe gaiviha

vi tagara livo hangge kunia. Nitun ratahigi

vi tagara livo hangvulu. Livo

keki vi tagarae batena ira tamana rav loli

sa ira havana rav lol bolololi.

(16) Be nitun atatu ngan nu hiruga gin bwanmemea

i boe take bilan

uteloloara dum i ginau duluai keki nu vahal

nituna, bwatuna nu hav lol te

didini rovoga lol talu sa nu hav lai te bilan

dura.

5)Hangge tamana mwa hora non nituna. Nora

mahalei bwanmemea, toa nu wehia

gabe tabwalugu nu vora. Tamana nu habwe boe

livo huba i boe gaiviha mulei

gi volin vavine. Tamana vi ngis gubwen gaiono

sa gaivwelu,(17) hohov

lalanggova huri ginaganiana i kea nu hahara

nituna huba lol gubwengi

duluai huri halan ginau duluai. Keki gaha

vi hora nituna vai aben

tamaragai vwate be vi haharae gin mataisao.

Kunia ngan mulei tabwalugu,

tamana nu haharae sa tamaragai vavine sa

tamaragai atamani. Lagia ran wehi

boe gi bigin vwavwaligi nu wehi dura ran

valinia la imwa. Dura vwaligi kea

ihana umu.

6)Hangge ira taman vavine, ninovi ran lalanggonggo,

be kera gaivasi rav

hanggo volin nitura bului tamana. Kera gaivasi

ram mai mai bwanmemea

gaivasi gi buluin non tamana nu nggol nituna

ginia. Ira bilan vwavwa ran

lai tabwalugu ram hiv an tahi sa hala behe

mwa hav iloe te be vaigougo vi

lagi, ta rav la vava rai votu kea vi gita

batoia ta si hav hudaligi tehe.

Amua tamaragai nu haharae ta nu vev dau huri

ute vai nongoiha. Mwarani

taman mwalanggelo mai ratahina raru lai bwanmemea

gaituvwa bari ivusi. Ta

hogosin mwalanggelo, be hogosina sibona sa

hogosina nitun tamana vwate,

kea vi lai bwanmemea vi hanggoe, i hogosina

vwate vi lai barimemea vi

hanggoe. Bwanmemea gairua gainggolen vavin

lagi vwate. Mwalanggelo vi

hunia gi bwanan ihei gaituvwa nin ira havan

tamana,(18) ta taman mwalanggelo

mai ratahina i tuan ira ratahin mwalanggelo

ran tomare ran hanggo bwana

ivusi nggolenggole gaibwalbwalo huri tabwalugu,teltele

huri mwalanggelo.(19)

7)Hangge ira atatun mwalanggelo ram botui

vanuan tabwalugu. Ira ratahin

mwalanggelo mai ira hogosina ram ban ram

du matbongon imwa.Taman tabwalugu

vi haroro la imwana aben tabwalugu vi uloinia

be mwei namen lingigo garigi

gom lagi nin imwadaru. Hangge huin tabwalugu

mwa ruru mwa dei.(20) Ira

hogosin atamani lagi ram lai bari gaituvwa

ram detel tabwalugu ginia, i

vwavwa bilan tabwalugu vwate vi tagahi dagai

barin tabwalugu gabe nu to

maia. Vwavwa kea mwa nggahalai ramun bari

gara la gaon tabwalugu. Gaon

tabwalugu mwasin gao wasi be unu sa gaovunga.Hangge

hogosin mwalanggelo vi

hagai bwanmemea gabe nu hanggoe. Vwavwa bilan

vavine vi vugeri bwana kea

vwavwa i tabwalugu ramuru du aten bwana ram

mai vai lol sara.

Tavaluna

9

1)Hangge taman vavine vi lai taiva vi hagainia

be ramen uvia.Taman tabwalugu

vi lai boe, nituna vi wehia vi ware ihana

be mitalai sa mwisale sa mitari

hano be ihan bilan vwavwa sa ihan tamana,

① Mitalaihuhu, kunia ihan

tamana Molhuhu, ② Mwisaleliliu, tamana Moliliu,

③ Mitaribani, tamana

Molbani, sa vi ware ihan havana vwate nu

mate huba tuai gabe vavine. Be

si motari kea nitun ratahigi Motariala, tamana

Viraala.(21) Tamana mwa avo

mwa hahara nituna mwa do aben boe mate i

tangbunia gabe ira tamana gailima

ran hogon bwana ninovi alolona. Gairuan tangbunia

non ratahin tabwalugu

kea nu taua mwa hen to dagai mau. Hangge

nogonan avoana taman tabwalugu be

nom vavine i masan tasalamwa nom tanga mwa

eno. Ta tanga gea damu gaituvwa

nu en aluna, hogosin mwalanggelo vi lai damu

vi gasia.

2)Ratahin mwalanggelo nu lai bwana, mwalanggelo

vi hunia la bwatuna vi uloi

ihan havan tamana vwate vi veve be bwanamwa

tata. Ira ratahin mwalanggelo

ram bugeri bari vataha bilan vwavwa.(22)

Vwavwa ram gaisigo gin ariu bwaro

ram huri atamani gabe mwalanggelo nu hun

bwanana. Ram bano, taman

mwalanggelo vi hanggo bwana vi tomuai mwalanggelo,

vwavwa ram huri

mwalanggelo. Rav dalis tabwalugu mai tamana,

tanga, damu, boe mate, rav la

dalisia varua rav harav bugin taman tabwalugu.(23)

Hogosin mwalanggelo vi

lai damu vi gasi aluna. Ratahin mwalanggelo

vwate vi ros tangbunia.

Ratahin vavine, ira tuana ram ros non tangbunia,

kea non vuvugeri alolona.

Lolovono lalai ira tuan tabwalugu, gabe daulato

dodolua ram lalagi

mwalanggelo lagi maira tuana dodolua.

3)Hangge kekhadogaha tatan atatu gailima

ram samara la hala. Vwavwa bilan

mwalanggelo ram samara mai nora teltele be

rav wehi ira ratahin

mwalanggelo maira hogosina, sa rav garuhira

gin wai sa bili sa taniavu.

Ira ratahin tabwalugu gabe ira tasalan tamana

dodolua ban dagai ram doron

be rav bulbul tagainira rav veve be kekea,

be ramen gan bwangon tabwalugu

sa rav hanggo huhuna. Ta vwavwa bilan tabwalugu

ram dul dagai ira ratahina

i tabwalugu mabutu alun bilan ira vwavwa.

Ira ratahina ram gele avoana non

tabwalugu nu togo gi vavin togo(24) radu

nu av leilei ira tasalan tamana

mai get marahi sa rovoga hahavwani sa vwangavwangan

boe. Ratahin tabwalugu

ram bugeri bwanmemea lalai vwavwa bilan mwalanggelo

huri teltele.(25) Ira

taman tabwalugu ram lai gaiviviligi huhugave

i dame, ihei nona 50 sa 100

mwa du la hala be vi wehi hei nin ira hogosin

vavine lagia. Ratahin

mwalanggelo vi vugeri bwana hangge vi ravae

na atatu gabe taman tabwalugu

(26) hangge rav siv langgao. Ira mwalanggelo

rituai havan lagi ram bosa rau

(27) mwa dabahu vava rav votu.

4)Hangge ira vavine ram samara liu ran votu

la vanua. Mwalanggelo vi tai non

gai, tamana vwate vi vahoe lol sara, gai

gailima gain boe, gain

lingilingiana varana vwate. Rav uv taiva

huri livon muan boe(28) gi matan

boe gabe tabwalugu nu wehia. La varan boe

gaivasi bilan atatu gaivasi ran

hogon bwana ninovi bului taman tabwalugu,

i raun longgo gailima sa gaiviha

gabe bwanmemea. Atatu lagi mwa doroi tuan

mwalanggelo gin bwatun boe mate

gabe tasalana nu wehia, vi toroi(29) tuana

ban dagai nin mwasin tuan

sibona.

5)Hangge mwalanggelo vi tu vi tau limana

alun gai muan boe aluna, tamana

vwate sa non ratahigi gabe mwasin havana(30)

vi avo aluna vi haharae gin

halan ginau rituai, sobe mwalanggelo bwatigoruga

vi hulu vagahia lol matan

sinobu be kea voso sa bugurana sa vonosleoana

sa nu hav rong te tamana mai

ratahina. Avoana vi nogo taman tabwalugu

gailima mai ratahina ram alo boe

mai dura, lingilingiana, raun longgo. Rav

aloe varua,rav harav bugin atatu

lagi. Taman tabwalugu vi vataha kera gaivasi

gin boe, vi vataha vwavwa

bilan tabwalugu gin bwana raun longgo. Ira

ratahin vavine,muana mwa bugeri

bwana gaituvwa sa gairua i bari gailima sa

hangvulu, vi taua la bwatun

tabwalugu, vi uloi ahoan tabwalugu be bwanamwa

tata malomwa gailima sa

hangvulu. Ira ratahina rituai rav vugeri

nora kunia rav tata duluai la

mwlanggelo vi ling ira tasalan bwaligana

gin boe i dura.(31)

6)Hangge vavine vi van la imwan ahoana. Hogosin

ahoana vi vora rau niu bwaro,

vi vohainia tabwalugu vi to alolona, ta ratahin

tabwalugu vi lai bari huri

rau niu kea. Ratahin tabwalugu vi vugeri

bwanan ira tuan mwalanggelo mai

ira hogosina, kera ngan gabe ram bului mwalanggelo

gin bilara ginaganiana

sa malogu sa bwana seresere memea. Longgo

vi manogo, mwalanggelo vi hun

bwanan atatun tamana vwate raru vi van la

imwa vi voro longgo. Ratahin

tabwalugu vwate vi varahi vatun umu ta kea

gabe nituna mwa dogo vi siv

lagi vai nongoiha. Ta varahi vatu mwa du

huri nitun vira mai motari be

motari nu vugeri seresere gailima i bari

memea vudolua, vira nu hogon

seresere hangvulu. Kea hanggea motari vi

hingge motari vwate vi varahi

vatu, binihiva be motari vi lol kunia batena

nituna vi lagi vai nongoiha,

kea vi lol kunia. Sinobu ram bisalsala nin

ira bwaligan mwalanggelo

gailima i tasalara gailima ram maturu vai

rani. Gabi vi oda vi wehi gara

toa gailima rav vugea. Ira lagi rav taura

la hala rav avo duleinira.

The Story of Raga

Chapter

8

(1)A sow gave birth to a boy and a girl,

and a sea snake had a male

child and a female child. They got married

to each other and had

their children. They are numerous together

with the descendants of a

giant clam and a white button shell. Although

the number of female

children was not known, the males slightly

outnumbered the females(1).

A married couple who had a baby boy seeks

for a pregnant woman. They

two give a piglet or a big red mat (to this

woman), and they let

their baby boy cut his young coconut.

In this way (it is said) he

cuts a young coconut with a pig or a big

red mat(2). A pig or a big

red mat given to the pregnant woman becomes

her debt(3). The coconut

(mentioned here) is not a real one but such

a phrase has a deep

meaning, that is, the starting point of everything

of a newborn was

from such a pig or a big red mat. The pregnant

woman is a relative of

(this) boy(4). (Now) she has given birth

to a baby.

2)If a newborn is a boy, the midwives shout

“U, U”in the same way as

one calls a canoe. If a girl, they say that

tasalana ata Ute taragaiana

(5) in such a big voice that people in

all houses can hear it.

Everybody knows that a newborn is a girl.

They bring a small red mat

and a child has it over its head and gives

it to her father's sister

(6) seriously because it has a serious meaning.

Suppose that when a

woman gives birth to a baby, there is her

father's sister's son. Her

father's sister will bring yams, will kill

a fowl, will cook them in

the earth-oven, will take them out of the

oven, and will give them to

her as her foods in the case that this woman

has given a female baby

and the child of her father's sister is a

boy. Everybody knows that

the father's sister's son of the woman (who

has just given birth to a

female baby) has secured this female baby

and that they two will marry

someday(7). Well, the woman who had a child

will lie down for ten days

and (on the tenth day) she will wash dirty

things from her

childbirth. The female child grows into a

girl called daulato when she

is ten years old or more, (then) her mother

finds out her father's

sister and unfolds(8) a big red mat in order

to give it to her, who

made mahalei and secured this girl(9). But the boy and

girl do not

marry yet. Even though the girl has known

the meaning of the big red

mat given by her mother, she is afraid of

the boy and is lalagi (to

him)(10) yet.

3)The father and mother of the boy prepare

three or five pigs, the first

of which has tusks growing up to its sideburns

i.e. bobibia, and five

or ten big red mats. Their child is going

to marry. In the side of the

girl(11), she performs a ceremony called

lihilihi(12). She gives a big

red mat to her father's sister or a highly

ranked female relative, and

this highly ranked woman operates her lihilihi. She purchases more than

ten or twenty things (in this ceremony).

If she is a child of a chief

(13), more than fifty. One of her fathers

brings a tusked pig which

she kills for a meal. If she is a child of

a chief, she kills mabu or

livoala(14). At night women beat the slit drums

and they make a tigo

dance till daylight. The father's sisters

of the girl let her bathe

in the sea. After coming back from the sea,

she kills a pig in order

to enter into the meeting house(15), and

she purchases everything in

front of the meeting house. (But) this is

the case of a daughter of a

chief only.

4)In the case of a daughter of the lower

ranked men, they prepare

everything in the house of her father and

she purchases (the following

things), ①ornament leaves attached in the

back called sori, ②a small

red mat or two small red mats, ③a dye, ④a

feather, ⑤ one, two or

three dried leaf umbrellas called bunbune, ⑥ a tusk of a pig which

she puts around her arm, or two tusks, the

number of which depends on

how many pigs she kills. A daughter of a

chief puts ten tusks around

her arm. She puts them in this way when her

fathers or her relatives

hold bolololi ceremonies(16). If she is a daughter of

an ordinary man

who is poor for red mats and pigs but who

has only his garden, he can

not give her a chance to take these things.

This is because he did not

work hard in his garden or he did not have

his sow.

5)Then the father of the boy sends a messenger

for him (to the father of

the girl). Their mahalei is a red mat and

a fowl which was killed when

the girl was born. The father of the boy

already found a tusked pig

and some other pigs for a bride wealth. He

takes six or seven leaves

out from the stem of cycad (Cycas circinnalis)(17), and he begins to

prepare for a banquet. He already taught

his child about the road of

everything on a past day. Now he sends his

child to an old person who

will confer knowledge on him. Same is found

with the case of a girl.

Her father or an old female person or an

old male person taught it to

her. On the day of marriage, they will kill

pigs for the meat cooked

in the earth-oven (in the meeting house)

and a sow will be killed

which was cooked in the earth-oven in the

house. A sow which is cooked

in the earth-oven is called umu.

6)Then the four (classificatory)fathers of

the girl who came together to

her village the previous day will get the

bride wealth of their child

with her (real) father. These four men came

here with four big red

mats which were supplemented to that of her

(real) father, who

prepares for (the marriage of) his daughter

with these mats. The

father's sisters of the girl took her to

the sea or any place and

(at that time) she does not know that she

will marry the following day.

They walk out and reach (the sea), then she

understands her

circumstances. But she does not ask about

it. (Because) the old

person already taught her about such a happening

in the future. Next

day, the father of the boy and his mother

bring one big red mat and

many small red mats. A sister of the boy,

who is his real sister or a

sister of the child of his another father,

will bring a big red mat

with her and another sister will bring a

small red mat with her. One

of two big red mats is used for an outfit

of the girl who are going to

marry. The boy will put the other big red

mat over his head and give

it to one of his classificatory fathers(18).

The father, mother, and

mother's sisters of the boy bring many big

red mats which are used for

(the payment to) the performance of whips

of the girl's side and that

of snakes of the boy's side(19).

7)Now the people of the boy arrive at the

village of the girl. The boy's

mothers and sisters go to the entrance of

the (girl's) house. The

father of the girl enters into her house

and he says,“My daughter, I

let you go today, you marry out from our

house.”Then she trembles and

cries(20). Sisters of the boy who is going

to marry bring one small

red mat and they put it to the waist of the

girl. And one father's

sister of the girl takes off the (old) small

red mat which has been

the loin clothe of the girl. This father's

sister of the girl puts

the fringes of the new small red mat into

her waist belt. This belt of

the girl is really strong vine, that is called

unu or another vine

called gaovunga. Then a sister of the boy will submit a

big red mat

which she have had (to the father's sister

of the girl). The father's

sister of the girl unfolds the big red mat

and puts it over her head

as well as the girl's head. With this big

red mat being put over their

heads, they go to the ceremonial ground.

Chapter 9

1)Now the father of the girl brings a trumpet

shell and hand it to the

those who blow it. He brings a pig and his

daughter kills it, which

results in her taking a name of Mitalai or Mwisale or Mitari so and so

named after her father's sister or her father

(for example;)①

Mitalaihuhu if her father's name is Molhuhu,②Mwisaleliliu if her father

is Moliliu, ③Mitaribani if her father is Molbani, or she will take over

the name of a female relative who was dead

long time ago. If (a woman

of the grade of) motari is a child of a chief and her name is Motariala,

her father is Viraala(21). (After she kills a pig,) the father

speaks

to and advises to his daughter who is standing

near the dead pig as

well as a big sack (woven of pandanus leaves)

into which her five

fathers put big red mats the previous day.

The second big sack which

is of her mother is placed a little away

from the first one. Then in

the end of his speech, the father of the

girl says,“Your woman, a pig

which your wife has killed, and your big

sack are there.” On the big

sack, there has been a yam which the sister

of the boy will take and

gnaw.

2)The mother of the boy brings a big red

mat which the boy puts over

his head. He calls the name of one of his

classificatory fathers and

says,“Your big red mat, my father.” The

mothers of the boy unfold a

small red mat for each of his father's sisters(22).

These father's

sisters walk with green reeds as their sticks

after a man to whom the

boy has given a big red mat by putting it

over his head. They walk.

The boy's father carries a big red mat under

his arm who is walking

ahead of the boy, after whom his father's

sisters walk. They turn

around the girl, her father, big sacks, a

yam, and a dead pig. They

turn around them twice and they lightly touch

the hem of the clothes

of the girl's father(23). The sister of the

boy takes a yam and gnaw

it. One mother of the boy shoulders one big

sack. The mother and

sisters of the girl shoulder their own big

sack in which their big

red mats and small red mats are placed. The

girl's sisters are seized

with sorrows. All of them are lalagi to the marrying boy as well as

all of his brothers.

3)Now five groups of people are mischievous

on the road. Father's

sisters of the boy are so mischievous that

they beat mothers and

sisters of the boy by snakes (being grasped

in their hands) or that

the former pours water, mud or ashes on the

latter. The girl's mothers,

who are wives of the girl's distantly related

fathers, try to bring

their faces close to the face of the girl

shouting kekea in order to

kiss her, or they try to grasp the girl's

breasts. But father's

sisters of the girl push them away and the

girl somehow goes to her

father's sisters. Her mothers throw back

her (own) words which were

uttered to them, when she was still a little

girl(24), that she would

not do such a thing as carrying a heavy basket,

working hard or

feeding pigs. Her mothers unfold big red

mats which are given to the

father's sister of the boy for the performance

of the snake-beating

(25). Her fathers bring whip-like branches

called huhugabe and dame.

Each of them who has fifty or an hundred

whips stands on the road in

order to beat anyone of brothers of the girl

who has just married. The

mother of the boy unfolds a big red mat and

the father of the girl

takes it(26). Then they pass by. Some of

young men who are relatives

of the married boy make a noise(27) by hitting

leaves on their rounded

hands until they reach (the boy's place).

4)Now Women are more mischievous. A party

reaches the village of the boy.

The boy cuts off branches and one of his

fathers sets them into the

ceremonial ground (as posts). Five posts

make one row which is called

the post of the pig and the other row is

called the post of

lingilingiana. They blow trumpet shells in order to show

the status of

the first pig(28) which is the substitute

of the pig the girl killed.

(The other) four pigs are fastened to the

posts of the (first) row,

which are given to four men who packed big

red mats in the girl's big

sack with her (real) father the previous

day, and (besides them),

there are five or so big red mats which are

called leaves of laplap

(raun longgo). The married boy gives the head of the

pig his wife killed

to his brother. He gives(29) it to his (classificatory)

brother who is

in a remote position far away from his true

brother.

5)Then the boy stands by and puts his hand

on the post to which the

first pig is fastened. One of his fathers

or his chief who is his true

relative(30) speaks to him and teaches some

moral principles to him.

If the boy is lazy, this man scolds him in

the public saying that he

is idle, he is like a shell, he is noisy,

or he does not listen to his

parents (but everything is finished today).

After his speech, five

fathers and mothers of the girl come and

turn around pigs, a saw,

lingilingiana, and big red mats called raun longgo. They round twice and

they touch the hem of the clothes of the

married man. The father of

the girl distributes pigs to these four men

and big red mats called

raun longgo to father's sisters of the girl. The first

woman among the

mothers of the girl unfolds one or two big

red mats as well as five

or ten small red mats, and puts them over

the head of the girl, then

calls the husband of the girl and says, “Your

big red mats, my father,

your g-strings are five or ten.” Some

of her mothers unfold their big

red mats in this way, to all of whom the

boy is related as their

father. The boy lets go these wives of his bwaliga with pigs and saw

(31).

6)Then the girl goes into the house of her

husband. The sister of her

husband breaks off a green coconut leaf and

throw it. The girl sits

down on it. The mother of the girl brings

(and gives) a small red mat

(to her) for this coconut leaf. The mother

of the girl unfolds big red

mats and gives them only to those brothers

or sisters of the boy who

helps him in preparing kava, food, or big

red mat. When the laplap is

finished, the boy puts a big red mat over

his head and gives it to

one of his fathers. They two go into the

house and they pour coconut

milk on the laplap. One of the mothers of

the girl treads on the

stones of the earth-oven of umu. This means that a child of this

woman will marry some day. But in the case

of treading on the stones

(in the marriage ceremony) of a female child

of vira and motari, motari

unfolds five big red mats and one hundred

small red mats and vira

(already) packed one hundred big red mats

in a big sack (in the day

of hohogonivwa.) In this way, motari will search another

motari who

will tread on the stones of the earth-oven

of umu. This means that

motari will do the same thing when her child will

marry some day.

People go home leaving five bwaliga of the boy and their five wives,

who sleep (here) until morning. The boy makes

fire and he kills five

fowls for their foods and he cooks them in

the earth-oven. (Then) the

married couple will see them off on their

way and say good-by to them.

Notes to Vevhurin Raga & The Story of

Raga

(1) From the beginning to this point, the

story is mythic. In “The Story of

Raga I”, Rev. Tevimule described the origin

myth, in which a giant clam

and a white button shell play important roles.

It is not clear why he

started the story of Chapter 8 with the children

of sow and sea snake.

(2) This is an idiomatic phrase concerning

infant betrothal. The phrase of

mwa dai simango gin boe sa bwana (mwa = he, dai = to cut, simango = a young

coconut which is filled with coconut juice,

gin = with, boe = a pig, sa =

or, bwana = a big red mat) is used when the parent

of a baby boy gives a

pig or a big red mat to a pregnant woman,

who calls the mother of the

boy vwavwa (father's sister), with intention that if

she gives birth to

a girl, they let marry their child to this

girl. See also Note 7.

(3) This also means that if the pregnant

woman gives birth to a girl, she

should “give” her child as a wife to the

boy who cut down a young

coconut, which results in the payoff of her

debt.

(4) The pregnant woman is nitu (mother's brother's daughter) of the boy.

See Figure in Note 7.

(5) The meaning of taragaiana is not clear. Ute is a name of place and is

changeable to another place name in this

phrase, such as tasalana ata

Gihage taragaiana.

(6) The meaning of hunia is “to put the end of an unfolded big red

mat over

one's head and give it to one's father or

father's sister”. This is

performed in hunhuni. See Section Ⅱ of Introduction.

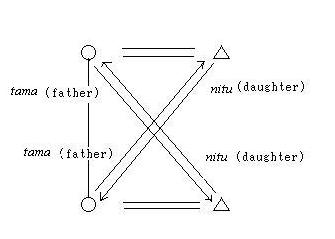

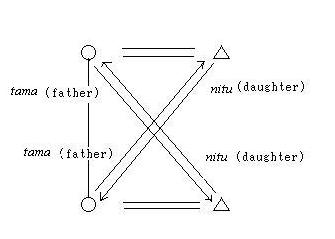

(7) In North Raga, a man can marry his mabi while a woman her sibi. The

situation is explained by the following figure.

A is a woman who has

just given birth to a female child. B is

her father's sister who has a

male child. B and her husband already gave

A a piglet or a big red mat

(mwa dai simango gin boe sa bwana). This time, B presents meals to A and C.

The father's sister's son of A is D who calls

C mabi.

(8) Vugeri (or bugeri) means “to unfold” ,which is used when

one unfolds a

big red mat in order to put the end of it

over the head of someone to

give it to his/her father or father's sister.

This is a scene of hunhuni

described in the Introduction.

(9) In the above figure, B gives meals to

A when A gives birth to a female

child. This meal is called mahalei.

(10) Lalagi (lala = to be afraid) is a kind of kinship term.

It is applied by

a woman to her sibi, that is, her potential husband.

(11)The male and female categories in North

Raga are shown in the following

table. Rev. Tevimule uses different categories

such as daulato, tabwalugu

and vavine to indicate the bride while mwalanggelo or atatu to indicate the

bridegroom. In this paper, however, I translate daulato, tabwalugu and

vavine as a girl if these terms refer to the bride.

In the same way,

mwalanggelo and atatu used for the bridegroom are translated as

a boy.

| male category |

female category |

glossary |

| naturimemea |

baby |

| naturigi |

hild |

| mwahiuboa |

huhugasbora |

male child whose voice

begins to break and female

child whose breasts

begins to grow.

|

| mwalanggelo |

daulato |

boy and girl |

mwaranggelo

or

mwalanggelo tuturu

|

tabwalugu |

boy who begins to have a

beard and girl who begins to

have the menses.

|

| atatu |

vavine |

general term for man and

woman

|

| bwatavwe |

old person whose hair

becomes white

|

| tamaragai |

very old person |

(12)Lihi means “to purchase”. Lihilihi is a woman's ceremony which seems to

be done before marriage. I will present a

detailed description of lihilihi

in “The Story of Raga V”.

(13)Ratahigi is translated as jif in Bislama, which means “chief”in English.

It is not a hereditary chief but a man in

the highest grade in the

graded system.

(14)See Figure 4 in Introduction.

(15)This is also woman's ceremony called haroroagamali (haroro = to enter, a =

into, gamali = meeting house). A woman who finished this

special

ceremony can enter into a meeting house freely

into which women are

generally prohibited to enter. I will describe

it in “The Story of Raga

V”.

(16)Bolololi is a ceremony concerning men's graded system.

Men can enter into

a higher grade by killing pigs and purchasing

several emblems in bolololi

ceremony. This will be described in “The

Story of Raga VI”.

(17)This is a traditional way of counting.

The literal translation of tamana

vi ngis gubwan gaiono sa gaivwelu is “his father will take off six or

seven days”.

(18)The meaning of havana is“one's relative”and although it is used

for

one's moiety members in some cases, it is

usually used for one's cluster

members. Havan tamana is thus usually used for the male members

of the

same cluster as one's real father. These

persons are also called

tama (father). In this way, havan tamana is translated as the

classificatory father.

(19)In Section 3 of Chapter 9, Rev. Tevimule

writes that the the father's

sisters of the bridegroom beat his mothers

or sisters by snakes while

the fathers of the bride beat her brothers

by whips. This is a kind of

bwaraitoa (joking behavior).

(20)Huin tabwalugu mwa ruru mwa dei literally means “ the bones of the girl

tremble and she cries”.

(21)There are four men's grades in North

Raga. The first grade is tari, next

moli, third livusi (or udu or nggarai), and the last vira. A man who got to

vira grade is called ratahigi, which is translated here as chief. A man

who is in any grade is given a name containing

the name of his grade.

For example, the name of a man in moli is Molmemea, Molture, Molhuhu and

so on while that of a man in vira is Viradoro, Virawahai, Viraala and so on.

(22)In this case, small mats are unfolded

on the ground, which are given to

the father's sisters of the boy. However

they are not put on the head of

the boy. The small red mat is not given in

the form of hunia except that

it is given together with the big red mat.

In the same scene of today's

marriage ceremony, the boy's father's sisters

are given big red mats,

not small red mats, in hunhuni. See Section Ⅲ in Introduction.

(23)When something is given in the ceremony,

the receiver makes this action.

Same is the case of hunhuni. A mat-receiver who is the father or the

father's sister of the mat-giver goes around

the giver a few times and

touches the edge of the clothe of him/her.

(24)Although I translate vavin togo as a

little girl here, vavin togo (vavin=

vavine = woman, togo = to stay) exactly means“a little girl

who does not

have an experience of being in love yet”.

(25)As was said in Note 8, the term bugeri (to unfold) is used in the scene

of hunhuni. In hunhuni in the marriage ceremony, it is usual that

if the

big red mat is given to the father's sister

of the bridegroom, the

bridegroom puts the mat over his head, which

is unfolded by his parents,

his mothers or his sisters. So the description

of Rev. Tevimule that the

mat is unfolded by the mother of the bride

is curious. This description

is also inconsistent with the writing in

Section 6 of Chapter 8 that the

parents and the mother's sisters of the bridegroom

prepare many big red

mats to give them to the performers of the

snake-beating as well as the

whip-beating.

(26)Here Rev. Tevimule writes that the mother

of the bridegroom unfolds a

big red mat which is given to the father

of the bride. Same curious

situation as in Note 25 appears. Because

the mat which is unfolded by

the bridegroom's mother is put on the head

of the bridegroom, which

should be given to his father or father's

sister, not to the father of

the bride. It is not clear whether the customs

described by Rev.

Tevimule here are of old days and are not

found today, or his

description is simply mistaken.

(27)Bosa rau is an action that one hits a leaf against

his palm by the other

hand in order to make an explosive sound.

(28)The literal translation of ram uv taiva huri livon muan boe is that “they

blow trumpet shells for the tusks of

the first pig”. There are many

kinds of rhythms and sounds of a trumpet

shell according to the status

of pig, that is, the grade of its tusks.

In this case, the status of pig

which is fastened to the first post is indicated

by the blowing of the

trumpet shell.

(29)Toroi (or doroi) means “to give something to eat in the

same way as

mwemwearuvwa which is a giving with expectation of return

gift (see

Introduction).” In this case, the brother

of the bridegroom who gets

the head of the pig is expected to give back

the same thing to this

bridegroom in the future in his own marriage

ceremony. Although the

receiver of mwemwearuvwa should be the giver's father or father's

sister, that of toroi is not limited to special relatives.

(30)Since havana(relative) usually means one's cluster member,

mwasin havana

(true relative) is used for genealogical

relatives or very close kin in

the same cluster.

(31)The mothers of the bride call the bridegroom

father(tama), while

the latter calls the former daughter(nitu). These women are the wives

of the fathers of the bride, whom the bridegroom

calls bwaliga.