THE STORY OF RAGA: A MAN'S ETHNOGRAPHY

ON HIS OWN SOCIETY (II) KIN RELATIONS

Masanori YOSHIOKA

INTRODUCTION

This is the second part of an English translation

of a hand-copied book

which was written in the“Raga" language

by the late Rev. David Tevimule in 1966.1)“Raga" is a language spoken by the

people of North Raga(northern part of Raga

or Pentecost Island) in Vanuatu. The work

consists of twenty chapters and concerns

various aspects of North Raga culture: its

origin myth, kin relations,initiation rite,

rank-taking system, chiefs, and customsconcerning

birth, marriage, and death. In this paper

I translate Chapters 6 and 7 in which Rev.

David Tevimule describes traditional kin

relations2) and explains the meaning of relationship

terms.

I

First of all, I summarize the materials

concerning North Raga traditional social

organization, relationship terminology and

marriage system collected during myfield

research there3).All of the people of North Raga are now

Christian. After the arrival of Christianity

the system was obliged to change in some

aspects.Information from different people

is sometimes confusing and in all,knowledge

of the traditional system is now possessed

only by a few people. One such knowledgeable

person is the Rev.David Tevumule, who is

said to be best versed in the traditional

kinship and marriage system. My materials

on such systems are mainly based on his information,

which is, of course, supplemented by that

from other knowledgeable people.

Social Organization

The population of North Raga is divided

into exogamous matrilineal moieties named

Tabi and Bule. Each moiety consists of numerous

named matrilineal descent groups. These descent

groups are classified into four larger groups

in each moiety, which have no names. I call

this kind of groupa cluster. Clusters are

discriminated from each other by the fact

that children of male members of each group

are named distinctly (Yoshioka 1985:29, Table

2). This group functions as the most corporate

group and as an exogamous unit in the alliance

system. In addition to these three social

groupings, there is the fourth grouping.

Each moiety is divided into two groups by

combining two clusters into one. I call this

kind of group a division. A division is not

a named group nor a corporate one, but functionsonly

in connection with the marriage regulation.

The North Raga social organization is summarized

in Figure I.

| Tabi(X) | Bule(Y) |

| | | |

Anserehubwe

a Agolomwele

etc.

A

Aarai

b Arevo

etc.

Atanbalo

c Atavalvusi

etc.

B

Amaao

d Avatgoho

etc. | Atalai

Labwao e

etc.

E

Aavauru

Avintena f

etc.

Atabulu

Avatgalana g

etc.

D

Anaronboe

Ansinai h

etc. |

* Anserehubwe, Agolomwele.. :names of

the descent groups.

* X , Y :moieties. * A - D :divisions *

a - h :clusters

Figure I

It is necessary here to explain some North

Raga concepts of kinship.

1)tavalu(na)4)means ‘a category' or ‘a party'. It sometimes

has the meaning of‘opposite'.In the context

of social organization, tavalui refers to a moiety.

2)vara(na) means ‘a category subordinate to tavaluna'. When it is used in the context of kinship

or social organization,it is exclusively

related to the matrilineality.It refers to

a matrilineal line, a matrilineal descendant,

or a matrilineal relation. People sometimes

translate it as a family. Moreover amatrilineal

descent group is referred to by vara. This term is also used to indicate the

cluster and the division, as well as,

in some cases, the moiety.

3)atalu(na) means ‘a side'. Ira ataluku, which literally means‘people of my side',is

basically used to mean‘my cluster member'.

It sometimes means‘my moiety member' especially in

front of the moiety members. When it is used

in an expression like“Inau atalun Vira Doro(I am a descendant of Vira Doro)",

it contains themeaning of bilateral descent.

4)atalavara(na) is used in the same way as ataluna. Atalavaraku has the same meaning as ira ataluku. Atalavaran Vira Doro has the same meaning as atalun Vira Doro.

5)hou(na) means ‘a line'. In the context of kinship,

it indicates bilateral descent. “Inau houhou Vira Doro" means “I am a bilateral descendant

of Vira Doro".

6)atalahou(na) is used in the same way as houhou.

7)hava(na) means “kin". Although one's hava mainly indicates his cluster member or his

moiety member, it also indicates a member

of the opposite moiety according to the context. Because

in North Raga kinship concept, every people

has some kinship relation with each other(See

‘Relationship Terminology').

The whole of North Raga is divided into

many named plots. The land-owing

unity is the descent group, each of which

possesses many plots, one of thesebeing recognized

as the group's place of origin and bearing

the name of the group itself. Its other plots

are scattered here and there in places not far

from this place of origin. People, whose

subsistence mainly depends on slash-and-burn

cultivation of taro and yam, are able to

cultivate any plots owned by any descent

groups in their own cluster.

A man should live on one of such plots of

his cluster after the death of his father,

although he is able to live on any plots

of this father's cluster (usually with his

father) during his father's lifetime. Since

the plots of the cluster are widely scattered

over the whole of North Raga5),thecluster is not localized. Moreover, it

should be noted that after the death of his

father, a man does not necessarily live with

his mother's brother. Hemay live on one of

many plots of his cluster, where his mother's

brother mayor may not live. Therefore such

a residence rule is avunculocal only in its

widest sense. Marital residence is virilocal.

Relationship Terminology

As known from the usage of the concept

of hava, which I have translated as kin,‘kin' does

not entail consanguinial relations. The consanguinial

kin is not terminologically differentiated

from fictive kin and every person of North

Raga is categorized by a certain‘kinship'

term. It is proper, in thissense, to use

‘relationship term' in place of ‘kinship

term'. I have listed relationship terms with

some of their genealogical specifications

in Figure II. These genealogical specifications

are extracted

1. ratahi(mua) MMM, M

2. tarabe(bena) MMMB, MB

3. aloa ZS(m.s.), ZD(m.s.)

4. tuaga(tuta, tuga) MMB, eB, eZ, MM

5. tua B(m.s.)

Z(w.s.)

6. tihi yB, yZ, SS(m.s.),

SD(m.s.)

7. hogosi Z(m.s.)

B(w.s.)

8. sibi(bena) MF, MFZS, MFZDS,

ZH, ZHZS, HB, HZS,

MFZ, MFSD, MFZDD,

ZHZ,ZHZD, HM

9. tama(tata) F, FZS, FZDS, ZDH

10.vwavwa FZ, FZD, FZDD, ZDHZ

11.mabi MMBWB, MBWB, WB,

MMBDS, MBDS, DS

MMBW, MBW, W, MMBDD,

MBDD, DD

12.nitu MMBS, WMB, MBS, S,

DDS

MMBD, WM, MBD, D,

DDD

13.ahoa H

14.tasala W

15.bwaliga WF, DH(m.s.)

16.habwe HZ, BW(w.s.)

17.bulena WB

18.huri FZH

*Terms in parentheses are only used in address.

*Terms such as aloa, tasala, bwaliga, and

bulena are used only by men.

*Terms such as ahoa and habwe are used only

by women.

*(m.s.) :Men's speaking.

*(w.s.) :Women's speaking.

Figure II

from genealogies which I collected during

my field research. Taking accout of the

reciprocal relationships between terms(shown

in Figure III), we can logically identify

more genealogical specifications of each

term.

A is reciprocal to B

━━━━━━━━━━━━━

A B | self-reciprocal term

━━━━━━━━━━━━━

C | self-reciprocal term |

| D |

ratahi --- nitu

tama --- nitu

vwavwa --- nitu

tarabe --- aloa

tuaga --- tihi

sibi --- mabi

|

hogosi

tua

bwaliga

habwe

|

bulena

huri

|

|

* Hogosi is used between different genders

while tua is used between people of the

same gender.

Figure III

Of eighteen terms listed in Figure II which

are used to refer to persons, all terms without

vwavwa are used with suffixed possesive particles

such as-ku(-u), -mwa and -na which mean‘my', ‘your' and ‘his(her)'respectively.

Tamau means ‘my father', ratahiku means ‘my mother', and taman ratahiku means ‘my mother's father'. These terms

are also used in address with such particles.

Terms in parentheses in Figure II are only

used in address and they are used without

possesive particles. Vwavwa is accompanied by a possesive particle such

as bilaku(my), bilamwa(your) and bilana(his or her).Bilak vwavwa means ‘my paternal aunt' and vwavwa bilan Tom means ‘Tom's paternal aunt'. Vwavwa is also used in address without the posessive

particles.(For a detailed description of

possesive particles, see Yoshioka 1987).

In daily life people sometimes use the

verbal definition of the relationship terms.

Some of such definitions made by a man are

shown in Figure IV. The verbal definition

is always made by thinking of a concrete genealogical

relation. A man defines ratahin ratahiku as tuagaku because he calls his real mother's real

mother tuagaku. In this sense, the verbal definition of

relationship terms is based on the genealogical

relation.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1. ratahin ratahiku =

tuagaku

2. taraben ratahiku

= tuagaku

3. taman ratahiku

= sibiku

4. ratahin tarabeku

= tuagaku

5. mabin tarabeku

= mabiku

6. nitun tarabeku

= nituku

7. ratahin sibiku

= sibiku

8. taraben sibiku

= sibiku

9. ratahin mabiku

= nituku

10. taraben mabiku

= nituku

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Figure IV

Although I have referred to the genealogical

relation, I should point out here that the

North Raga terminology as a system is not

based on one's genealogical relation but

one's affiliation to the social group, that

is, the cluster. The verbal definition mentioned

above is valid only within a scope of genealogy.The

table of relationship terms with their genealogicalspecifications

is also used to analyse the terminological

system only withinthe scope of genealogy.

Moreover, in the North Raga system there

is not always a one-to-one correspondence

between relationship terms and genealogical

relations. For example, a man who is ego's

FFBDS is referred toby the term tama if he belongs to the same cluster as ego's

father while he is referred to by the term

sibi if he belongs to the same cluster as ego's

mother's father(Yoshioka 1985:35). This is

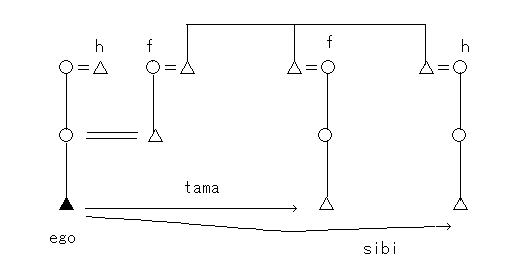

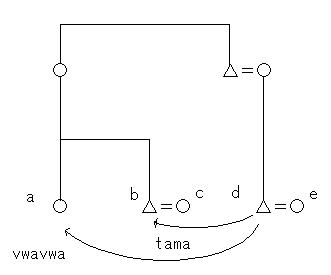

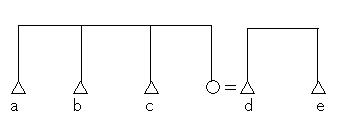

shown in Figure V.

*‘f' and‘h' are clusters.

Figure V

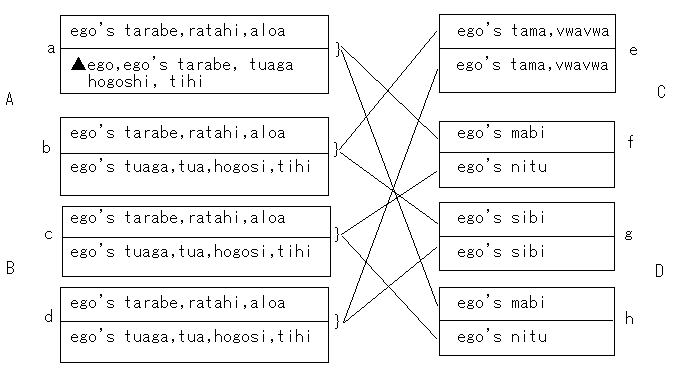

The relationship between terms and clusters

is shown in Figure VI, which

ndicates that people in the opposite moiety

are categorized according to their affiliation

to the cluster. It should be added here that

all men who belong to the cluster‘e' have

bwaliga relation to all men who belongs to the cluster‘g'

while all men in the cluster‘f' have bwaliga relation to all men in the cluster‘h'.Therefore

ego's tama is bwaliga to ego's male sibi, and ego's male mabi or nitu in one cluster is bwaliga to ego's male mabi or nitu in the other cluster.

X Y

|

▲ male ego

(who belongs

to the cluster

‘a'.)

ego's ratahi,

tarabe, tuaga,

tihi, tua,

hogosi, aloa

|

| |

ego's tama,vwavwa

|

ego's mabi-nitu

|

ego's sibi

|

ego's mabi-nitu

|

| |

* This figure shows the case

in which ego belongs to the

cluster ‘a' and his real

mother married a man of the

cluster ‘e'.

* Letters of the alphabet

correspond to those in Figure I.

* mabi-nitu shows that mabi

and nitu are placed in

alternate generations in

the matriline.

Figure

VI

Although those who are in the same moiety

as ego are terminologically classified by

the principles of generation and sex regardless

of their affiliation to the cluster6)(see Figure VIII), men in the same cluster

as ego have bwaliga relation to men in one cluster of the other

division in thesame moiety. For example,

ego's tarabe in ego's cluster has bwaliga relationto ego's tarabe in one cluster of the opposite division.

In this case, the child of the former is

called nitu by ego while the child of the latter is

called mabi. Such a mechanism will be further explained

in the following.

Marriage System

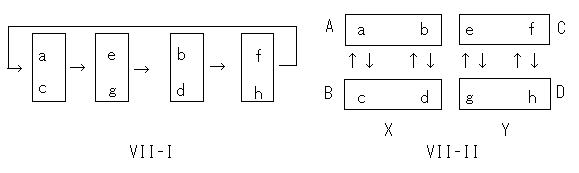

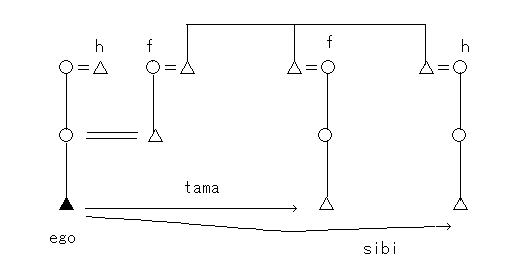

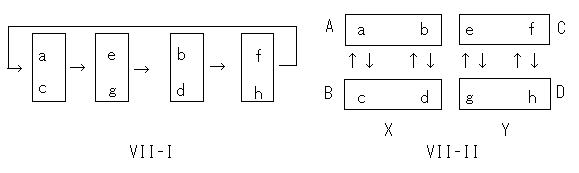

I have already analyzed the marriage system

of North Raga in a previous paper, where

I showed that there are two kinds of alliance

system in North Raga (Yoshioka 1985). One

is the asymmetric system between clusters

which is based on the sister-exchange(Table

VII-I). The unit of the asymmetrical alliance

is a pair of clusters whose male members

are bwaliga to each other. The other is the symmetric

system between clusters which is based on

the daughter-exchange(Table VII-II). Men

who are bwaliga to each other exchange the daughter of each

other in marriage. The marriage regulation

underlined in the former system is expressed

by people as follows: a man should marry

his female mabi and a woman should marry her male sibi, while such a regulation underlined in the

latter system is expressed as follows: a

man in one division in a moiety should marry

a daughter of a man who belongs to the other

division in the same moiety.

* Letters of the alphabet correspond

to those in Figure I.

* Arrows indecate the direction

of the movement of women at

marriage.

Figure

VII

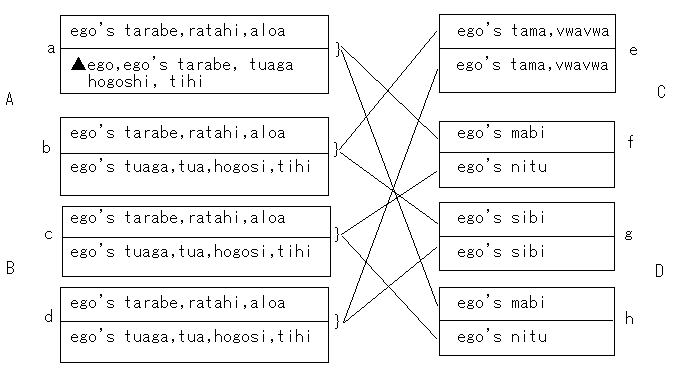

The North Raga marriage system in connection

with the relationship terminology is summarized

in Figure VIII. In it:(1)All tarabe, male tuaga, tua, male tihi and aloa in ego's cluster‘a' marry ego's female

mabi in the clusters ‘f' and‘h'.(2)All tarabe, male tuaga, tua, male tihi and aloa in cluster‘c' marry ego's female

nitu in ‘f' and ‘h'. Those men who have married

ego's female nitu are called bwaligaku. (3)All tarabe, male tuaga, tua, male tihi and aloa in cluster‘b' marry ego's vwavwa( cluster ‘e') in one of the alternate generations

and to ego's female sibi(cluster‘g') in one of the alternate generations.

(4) All tarabe, male tuaga, tua, male tihi and aloa in cluster ‘d' marry ego's vwavwa in cluster ‘e' of the other alternate

generations and ego's female sibi in cluster ‘g' of the other alternate generations.Those

men who have married ego's vwavwa are called huriku.(5)All of the male members in ego's cluster

refer to ego's mabi and nitu as mabi and nitu respectively. But for tama, vwavwa, and sibi, a different situation exists. Those in

ego's alternate generations refer to ego's

tama, vwavwa and sibi by the same terms as ego while those in

the opposite alternate generations refer

to ego's tama and vwavwa as sibi and ego's sibi as tama or vwavwa.(6) Men in the clusters‘a' and ‘c',‘b'

and ‘d',‘e' and ‘g', ‘f'and ‘h' are

bwaliga to each other. Those whom the former in

the pair call mabi are called nitu by the latter.

Moiety X

Moiety Y

* Letters of the alphabet corespond

to those of Figure I.

* Central lines in the boxes divide

alternate generations.

* ------ means marriage between

male member of the moiety X

and female member of the

moiety Y.

Figure VIII

The relation between wife-giver and wife-taker

is shown in Figure IX.All male members of

ego's cluster marry ego's female mabi while female members in the same alternate

generations as ego in ego's cluster marry

ego's sibi and those in the other alternate generations

marry ego's tama.

Mabi-Nitu's

Ego's Sibi's

Cluster

Cluster Cluster

|

|

ego's mabi

- - - - - - --

ego's nitu

──────

ego's mabi

- - - - - - --

ego's nitu

|

|

───→

───→

|

|

▲ego

ego's tua

tuaga,tihi

hogosi

- - - - - - -

ego's

tarabe,

ratahi,

aloa

|

|

|

ego's sibi

──────

ego's tama

vwavwa

|

|

|

Mabi-Nitu's Cluster

Tama's Cluster

WIFE-GIVER

EGO WIFE-TAKER

* The arrows indicate the direction

of the movenent of women at marriage.

* - - - - - divide alternate

generations.

Figure IX

II

In this section I briefly comment on the

kinship and marriage system in today's situation.

As already said, the traditional system has

changed in some aspects and some knowledge

about it has been lost.

Even now it is a common recognition that

the moiety is exogamous, and it is easy to

find a man who knows that each moiety is

divided into two divisions. But people are

confused about how many clusters there are

in each moiety. One of the reasons for such

confusion may be that although in the traditional

system children of male members of each cluster

were distinctly named,adopting Christian

names caused the naming system to change.

Now only some persons have such names as

their personal names. Moreover, many people

do not know all the names of the descent

groups in their own cluster. The relation

between descent groups and cluster is explained

in the myth. But the details of such a myth

have been forgotten.

Among the factors which caused confusion

in the social grouping, the most influential

one is the change in the marriage system.

Although the moiety exogamy is rigidly obserbed

even now, it happens that a man marries to

his vwavwa, his sibi and even his nitu. The vwavwa marriage is most prevalent among these ‘incorrect

marriages', while nitu marriages are very few. Such marriages cause

confusion in the terminological system because

thelatter's structure depends on the mabi marriage. When the terminological system

is confused, the system of social grouping

becomes confused because the latter has the

harmonious relation with the former in the

traditional sysytem. For example, traditionally

all male members of one's father's clusterwere

one's tama but the vwavwa marriage has made it possible to find his

nitu and mabi in that cluster(Figure X).

* T = tama, V = vwavwa, M = mabi, N = nitu

* When ego marries correctly, he refers to

persons in his

father's cluster by the terms in parentheses.

Figure X

Even now people insist that ego in Figure

VIII should marry a daughter of a man of

division ‘B'. When ego marries a daughter

of a man of cluster‘c',no confusion occurs,

but when he marries a daughter of a man of

the other cluster in division ‘B', a vwavwa marriage and a sibi marriage occur. Traditionally ego's bwaliga is a man who has married his nitu. But if ego marries his vwavwa, he becomes bwaliga of the latter's father and reciprocally

he refers to him as bwaliga, who had been his huri. Because of vwavwa marriage, ego's bwaliga may become the same person as ego's huri, whoshould belong to a diffent cluster from

that of ego's bwaliga. In today's situation, these two clusters

become amalgamented.

The terminological system itself is undergoing

change.In my first research in this area

in 1974 I never heard the word ‘tawean',

which is Pidgin English. But during my second

reserch there from 1981 to 1982 I often heard

this word used by the younger generation.

Tawean means‘brother-in-law'. A wife's brother

as well as a sister's husband are referred

to by tawean. This usage has resulted in

the confusion of mabi and sibi. Some persons said that mabi and sibi are the same and that it is correct for

a man to marry his sibi.

The intrinsic character of the traditional

terminological system has also contributed

to the present confusion. In the traditional

system the genealogical relationship should

not be extended to the classificatory relationship

(by which I mean here the relationship outside

genealolgy).As already seen, one's genealogical

tarabe has a completely differnt role from the

classificatory tarabe. The marriage with a daughter of one's classificatory

tarabe in a certain cluster is correct while the

marriage with daughters of his tarabe in the other clusters is not correct. But

if a man gives importance to the genealogical

relations and extends it to the classificatory

relation, he may insist that I marry correctly

even if hemarries a daughter of his classificatory

tarabe in his division.

III

In the text of Father David the traditional

kin relations are described.I supplement

it here by pointing out the characteristic

relationship among kin in today's situation.

Tarabe in ego's cluster(for example ego's mother's

brother)is the propertygiver to ego because

the inheritance rule is matrilineal. But

he is not an authorized person and the jural

authority over a man or a woman in marriage

is vested not in his or her tarabe but in tama(real father or classificatoryfather if he

is dead). In North Raga there is no tentioned

relationship between tarabe in ego's cluster and ego such as reported

in the other matrilineal societies. There

is also no tentioned relationship between

ego and the other kin in ego's moiety without

huri. Huri is the husband of vwavwa. Huri should be an authorized person to ego because

it is said that when one's huri came near him, he ran away. Now such a custom

has been lost.

Tentioned relationship is found between

ego and sibi. Some restrictions are placed on ego's

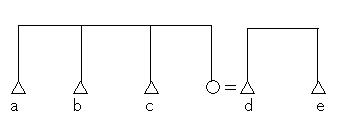

behavior toward his or her sibi. This is described in Father David's text.

Conversely, ego's mabi should observe some restrictionsin front

of ego. When ego marries one of his female

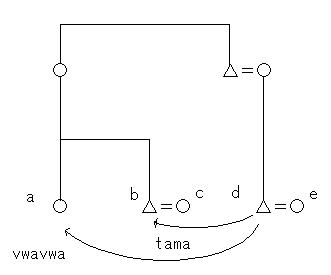

mabi, ego calls her brothers bulena(Figure XI). It is not necessary for ego

to assist his bulena while bulena should assist ego on any occasion.

*‘d' calls ‘a',‘b', and‘c'

bulena while they call d' sibi.

*‘e' calls ‘a',‘b', and‘c'

mabi and they call‘e' sibi.

Figure XI

It is said that members of the same moiety

should help each other. Especially,men who

call each other bwaliga should do so. Bwaliga should give assistance to each other on

any occasion such as ceremonial exchanges,

building of a new house, or making a new

yam field and so on. Even if it happens that

tarabe in ego's cluster marries incorrectly ego's

female nitu, such a tarabe is treated as ego's bwaliga and should behave as ego's bwaliga.

Joking behavior or funny talk is called

vwauvwau. Vwauvwau is permitted between a woman and her husband's

classificatory father(tama) or father's sister(vwavwa),or between a man and his classificatory

father. See Figure XII. Suppose ‘d' gets

angry with‘e'on some occasion. ‘e' tells

him that she is leaving home. But actually

she hides in some place near the house. ‘d'

searches for her here and there and at last

finds her near the house. In such a case,

‘e' can talk with ‘a' and ‘b' about it

and they can laughat‘d'. In other words,

those who can laugh at a man by talking about

a happening between him and his wife which

disgraces him are only his tama and vwavwa, besides his wife. It is also said that

‘b' can talk with ‘d' about‘c''s funny

episode such as the above. It is also said

that ‘a' can take the hand of ‘e' and let

it touch the hips of the former. When ‘a'

does so,she will make bwaraitoa to‘d' on the occasion of‘d''s rank-taking

ceremony.

Figure

XII

Bwaraitoa has the same meaning as vwauvwau and people say that these two are the same.

But it seems that bwaraitoa is used often on a ceremonial occasion while

vwauvwau is used in everyday life. Bwaraitoa is observed on three occasions at least.

The first is when a child is born. In this

case, a child's classificatory tama and vwavwa steal some property of the child's real

tama and sometimes the former put a taboo on

the latter's cultivation or other things.

The second is the marriage ceremony. In this

case, the vwavwa of the bridegroom acts funny with his ratahi;for

example, the former sprinkles water or mud

on the latter. These vwavwa are given red mats called bwana7) (a kind of traditional money) by the parent

of the bridegroom. The third is the rank-taking

ceremony. In this ceremony, a man needs many

pigs,which are given by some men at the ceremony(8). When the man who is given pigs dances on

the ceremonial ground in order to receive

such pigs, his classificatory tama or vwavwa dances jokingly following him. This is bwaraitoa in this case. After that the man's wife or

his mother should give red mats or small

red mats called bari9) to those who did bwaraitoa10).

In North Raga, generaly speaking, the wife-taker

is in a superior position to the wife-giver,taking

account of the following facts:that the wife-takers

of ego'scluster are ego's sibi and tama; that one should observe many restrictions

in front of his sibi; that one's tama has jural authority over him;and that one's

tama or vwavwa has the right to laugh at him and make funof

him. As already said, tama and sibi of male members in ego's alternate generations

in ego's cluster are called sibi and tama respectively by male members in the opposite

alternate generations, and tama and sibi of the latter are called sibi and tama respectively by the former. The general relationship

between wife-taker and wife-giver is summurized

as shown in Figure XIII.

Figure XIII

IV

In this paper, I present Father David's

Raga text with an English translation. His

original text is not spoken one but written

one and it seems to contain many writing

and spelling mistakes. I made many correctionswith

the collaboration with Mr. Richard Leona,who

is a native speaker of the Raga language

and who was my collaborator in the work of

this translation. Although in my earlier

paper titled“The story of Raga (I)"

I presented the original writing with corrected

writing, in this paper I present only a corrected

version of the text. Colons and periods in

this text are not always in the original.

They are sometimes omitted, or exchanged,

or supplemented in order to clarify the relationship

between the original and its translation.

I have also omitted the original parentheses

in the text to avoid a complexity.

Some words in the parentheses in the translation

are supplemented by me to clarify the meaning

of the original sentence. When the Raga word

is used in the translation, I show its English

translation in a bracket or explain its

meaning in a footnote. As for the footnotes,

those in the text are common with those of

its translation.

Notes

1)In “The story of Raga(I)", I treated

the first two sections of Chapter 6 of

the original as sections 8 and 9 of Chapter

5. Therefore section 1 of Chapter 6 in this

paper is originally section 3 of Chapter

6.

2)I wish to express my gratitude to Mr. P.E.

Davenport of Shinshu University who read

an earlier version of this paper and improved

my English.

3)I was engaged in field research in North

Raga in 1974, from 1981 to 1982, and again

in 1985.

4)na is a possesive particle of the third person

singular.

5)In the case of the cluster‘a' which contains

many descent groups such as Anserehubwe,

Agolomwele, Lolkoi and so on, the plots of

Anserehubwe are scattered in the northernmost

part, the plots of Agolomwele in the north-east

part, and those of Lolkoi in the central

part, and so on.

6)Ego's SW belongs to the same moiety as

ego.But she is categorized as mabi. For the discussion of this, see Yoshioka

1985.

7)See footnote 23 in the text.

8)This is a part of the ceremonial exchange

done in the series of the Bolololi ceremony.

For detail description, see Yoshioka 1983a,1983b,

and 1986.

9)See footnote 21 in the text.

10)I will present a detail description of

bwaraitoa in the following parts of this paper.

References

Yoshioka,M

1983a Bororori I - Hokubu Raga ni okeru

buta ni matsuwaru gishiki -. (Bolololi I

- A Ceremony Centering Around Pigs in North

Raga -.)Annual Review of Social Anthropology 9:167-190.

1983b Bororori II - Hokubu Raga ni okeru

riidaashippu -. (Bolololi II -Leadership

in North Raga -.) Japanese Journal of Ethnology 48:63-90.

1985 The Marriage System of North Raga,

Vanuatu. Man and Culture in Oceania 1:27-54.

1986 A Report on Bolololi: Rank-taking

Ceremony in North Raga, Vanuatu.(Unpublished.

A report dedicated to the Vanuatu Cultural

Centre.)

1987 The Story of Raga: A Man's Ethnography

on his Own Society(I) The Origin Myth. Journal of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Shinshu

University 21:1-66.