The Story of Raga: A Manfs Ethnography on His Own Society (VI): Rank-taking Ritual

Masanori YOSHIOKA

INTRODUCTION

This is the sixth part of an gexperimental

ethnographyh entitled gThe Story of Raga,h

which consists of a text written in Raga

(the language of North Raga) by the late

Rev. David Tevimule in 1966, with its English

translation. An introduction is also provided,

describing the data collected during my field

research on the same topic.

The original title of David Tevimulefs text,

which was written in the form of a hand-copied

booklet, is Vevhurin Raga, which means gThe Story of Raga.h It consists

of twenty chapters and concerns various aspects

of North Raga culture: its origin myth, kin

relations, rank-taking ritual, chiefs, certain

rituals for boys and girls, and customs concerning

birth, marriage, and death. In this paper,

I translate Chapter 14 in which David Tevimule

describes the rank-taking ritual, which is

related to the public graded society.

The islands in Northern Vanuatu were known

to anthropologists in the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries as an area

where the so-called gsecret societyh as

well as the gpublic graded societyh existed

(cf. Codrington 1891, Rivers 1914). Anthropologists

studying Vanuatu during that time were mainly

interested in the former type of society,

and thus information concerning the graded

society was incomplete. In contrast, in the

later twentieth century, the public graded

society became one of the main themes for

Vanuatu anthropology and detailed studies

were made (cf. Allen 1981). I also examined

the graded society of North Raga in detail

in my ethnography on North Raga based on

my field research1 (Yoshioka 1998). In this paper, I describe

the ritual aspects of the graded society

of North Raga.

1 Pigs

Pigs (boe) play an important role in the rank-taking

ritual called Bolololi. Pigs are the most valuable exchange goods,

and the main purpose of the Bolololi ritual is to kill pigs and purchase several

insignias by paying in pigs. Pigs are mainly

divided into sows (dura), bisexual pigs (ravwe), and boars. The latter two kinds of pigs

have tusks and the bigger the tusks are,

the more valuable the pigs are considered.

Although the bisexual pigs played important

roles in the past because their tusks were

bigger, it is currently said that such pigs

no longer exist in North Raga. Therefore,

boars play important roles in todayfs Bolololi. Hereafter in this paper, the term gpigh

refers to a gboar.h

There is no special name for a boar in the

Raga language, so the word indicating all

kinds of pig, boe, is used to refer to a boar. Boe is broadly classified into two categories.

One is udurugu, which refers to a boar not yet castrated,

and the other is bovtaga, which refers to a castrated boar. The boar,

sometime after birth, begins to grow tusks

called basina from its upper jaw. The pig at this growth

stage is called udurubasiga; it is considered ready for castration and

its basina tusks are extracted. The basina are extracted because they hinder the growth

of the tusks growing from the lower jaw.

These tusks, called livo, mark the value of the pig. It is said that

boars should be castrated; otherwise they

will fight each other and break the valuable

livo tusks.

The numbers in Table 1 refer to the gkindh

of classified boars. Pigs from no. 1 to no.

4 are classified as udurugu, whereas those from no. 5 to no. 26 are

bovtaga. The tusks from the lower jaw grow in an

arc shape at the stage of bobibia (no. 11) and the top of the tusk may touch

the cheek. At that point, the cheek is cut

so that the tusk may grow through the cheek

smoothly. The tusk grows in the shape of

an arc and the tip eventually reaches the

lower jaw again. Then the tooth of the lower

jaw, which touches the tip of the tusk, is

extracted. In this stage, the tusks of most

pigs stop growing because their tips reach

the bone of the lower jaw and cannot easily

continue to grow. There are few pigs with

bigger tusks than livoaltavaga (no. 17). Only some pigs whose tusks grow

without touching the lower jawbone reach

the stage of livoalbasiga (no. 18). It is said that now there is no

man who has ever seen a pig with a bigger

tusk than livoallivoa (no. 22).

Table 1@Class and kind of pig

|

class and name

|

kind and name

|

glossary

|

|

|

A udurugu

|

1 lahoa (lahoa = testicles)

2 botuguana (bo = pig, tugu =to join with a rope)

3 udurugu (duru = to block)

4 udurubasiga (basina = a tusk growing from the upper jaw)

|

a pig that has testicles

a pig that is tethered by a rope

a pig that goes anywhere

a pig that has basina

|

|

|

B bololvaga

|

5 bololvaga (lol vana = in the mouth)

6 langvonosia (lango = fly,

vonosia = to alight on it)

7 bogani (gani = to eat)

|

a pig whose tusks are inside the mouth

a pig whose tusks are invisible when a fly

alights on them

a pig whose tusks* are visible when the pig

eats and opens its mouth

|

|

|

C tavsiri

|

8 tavsiri (tai = to cut, siri = to scratch)

|

a pig whose tusk breaks the upper lip

|

|

|

D bobibia

|

9 bolivoa (livo = a tusk)

10 bohere (here = to swing by wind)

11 bobibia (bibia = to reach)

|

a pig who has its tusks

a pig whose hair reaches its tusks when the

wind blows

a pig whose tusks reach its cheeks

|

|

|

E mabu

|

12 livbwanbwana (livo = tusk, bwana = large red mat)

13 mabu ( mabu = to rest)

|

(the meaning is not known)

a pig whose tusks reach the boneoof the lower

jaw

|

|

|

F livoala

|

14 huimosi (hui = bone, mosi = to break)

15 nggoletirigi or livoalnggole tirigi (nggole =to prepare,tirigi=a little)

16 nggolelavoa or livoalnggolelavoa

(nggole =to preapre, lavoa = big)

|

a pig whose tusks go into the bone of the

lower jaw

a pig whose tusks are preparing to again

grow up a little from

the lower jaw

a pig whose tusks are preparing to extend

greatly from the lower jaw

|

|

|

G livoaltavaga

|

17 livoaltavaga (tavaga =to split into two parts )

|

a pig whose tusks grow long enough to split

the bone of the lower jaw

|

|

H livoalbasiga

|

18 livoalbasiga (livoala + basina)

|

a pig whose tusks form a circle and starts

to grow the second set of tusks like the

number-4-type pig

|

|

|

I livoallolvaga

|

19 livoallolvaga (livoala +lolvaga)

|

a pig whose tusks form a circle and starts

to grow the second set like the

number-5-type pig

|

|

|

J livoalgani

|

20 livoalgani (livoala + gani)

|

a pig whose tusks form a

circle and starts to

grow the second set like the number-7-type

pig

|

|

|

K livoaltavsiri

|

21 livoaltavsiri (livoala

+tavsiri)

|

a pig whose tusks form a circle and starts

to grow the second set like the number-8-type

pig

|

|

|

L livoallivoa

|

22 livoallivoa (livoala + livoa)

|

a pig whose tusks form a

circle and starts to

grow the

second set like the

number-9-type pig

|

|

M livoalhere

|

23 livoalhere (livoala + here)

|

a pig whose tusks form a

circle and starts to grow

the second set like the

number-10-type pig

|

|

N livoalbibia

|

24 livoalbibia (livoala + bibia)

|

a pig whose tusks form a

circle and starts to grow

the second set like the

number-11-type pig

|

|

O livoallivbwanbwana

|

25 livoallivbwanbwana

(livoala+livbwanbwana)

|

a pig whose tusks form a

circle and starts to grow the second set

like the number-12-type pig

|

|

P livoalmabumulei

|

26 livoalmabumulei (livoala

+ mabu, mulei = again)

|

a pig whose tusks form a circle and starts

to grow the second set like the number-13-type

pig

|

|

*Pigs have two tusks growing from the lower

jaw. Sometimes one of the tusks grows quickly

and becomes bigger than the other. In this

case, the kind of the pig may be adjusted

according to the size of the bigger tusk.

|

Since the pigs are classified according to

the rough size of the

tusk, it is difficult to exactly determine the kind

of pig. That is, there are no strict criteria

by which to differentiate, for example, bololvaga (no. 5) from langvonosia (no. 6). However lahoa (no. 1) can be clearly differentiated from

langvonosia (no. 4), which is in turn decidedly regarded

as different from tavsiri (no. 8). This is because lahoa has no tusks whereas langvonosia has tusks, and the tusks of langvonosia do not grow outside the mouth whereas those

of tavsiri do. According to such concrete indices,

certain kinds of pigs are combined into a

class. People call pigs from no. 1 to no.

4 udurugu (class A) and pigs from no. 5 to no. 7 bololvaga (class B). The class of tavsiri (class C) is composed of only one kind of

pig. The class of bobibia (class D) is differentiated from tavsiri by the former having arc-shaped tusks and

the latter having straight tusks that have

not yet begun to curve. The pigs in class

E, mabu whose tusks reach the lower jaw, are clearly

differentiated from the pigs in class F,

livoala, because the tusks in class F do not stop

growing at the lower jawbone (i.e., the tusks

continue to grow).

Although classes are clearly delineated,

numerous disputes occur regarding the classification

of pigs. For example, it is often disputed

whether a pig whose tusks have just begun

to curve is in class C or D. In one case,

a pig that was declared to be in class F

was given to a man, but after slaughtering

this pig, he found that its tusks did not

grow over the lower jawbone. In such a case,

the claim by the giver of the pig is usually

maintained and the receiver can only grumble

about it.

2 Outline of the Bolololi Ritual

Codrington reported that the name of the

public graded society in North Raga was Loli (Codrington 1891:114), whereas it was called

Suqe in the Banks Islands and Huqe in Ambae (Codrington 1891:104, 113). It

seems strange that the name in North Raga

would be completely different from those

in other parts of Vanuatu. During my field

research, I did not find any name for the

graded society. It seemed that people might

not think that the graded system can be considered

a gsociety,h and I found only that people

call the ritual concerning the graded system

Bolololi.

As shown in Table 2, in North Raga there

are presently four grades for men, named

from lowest to highest as tari (meaning gto lay the foundationh or ga

male child or sonh), moli (whose meaning is not known to the people),

livusi (meaning gto climb over the hillh), which

is also called udu (meaning ghalfh) or nggarai (meaning gto get overh), and vira (meaning ga flowerh). To enter the upper

grade, it is necessary to kill pigs of a

prescribed class and prescribed number as

well as to purchase certain kinds of insignia

by paying in pigs of a prescribed class and

number. A man who enters the last grade vira is called ratahigi, a traditional political leader translated

as jif (chief) in Bislama, Vanuatu Pidgin.2 It is necessary to kill a pig of class B

to enter the first grade tari and to kill a pig of class C or D to enter

the second grade moli. Although people kill pigs in these cases

in a fixed fashion, special rituals are not

settled. Those who enter these grades are

usually children whose fathers make them

kill pigs to be served as side dishes during

feasts. After this, the child enters the

grade of moli. He should then purchase a special insignia

during his tenure in the moli grade, and this performance should be done

in a special ritual. This is the first Bolololi. The ritual has many variations according

to which grade is to be entered or what kind

of insignia is to be purchased. Bolololi is a general term indicating the series

of these rituals.

Table 2 Grade and pig-killing today

|

grade

|

pigs to be killed to enter the grade

|

specific pig-killing required while in a

particular grade

|

|

|

class

|

number

|

name

|

class of pig

|

number

|

|

tari

|

B bololvaga

|

1

|

----------

|

------------

|

---------

|

|

moli

|

C tavsiri or

D bobibia

|

1

|

----------

|

------------

|

----------

|

|

livusi

(udu,

nggarai)

|

E mabu

|

1

|

sese

|

any class

|

10

|

|

vira

|

F livoala

|

1

|

mabuhangvulu

|

mabu

|

10

|

Certain characters appear and play important

roles in Bolololi rituals. One of them is the man who will

kill pigs and purchase insignias in the ritual,

referred to as a novice or ga central figure.h

He is the chairperson of the Bolololi ritual as well as of the feast held after

Bolololi. Preparations for a Bolololi usually begin 10 days before the ritual

and are made in cooperation with residents

of the village where the Bolololi will be held, for whom feasts of dining

and drinking kava3 are held every day until the day of Bolololi.

Although the yams and taro used in the feasting

are brought by the villagers, the side dishes

and kava are served by the central figure

of the Bolololi. When the ritual is approaching, a big shelf

is made, on which the central figure heaps

up yams or taro for the feast on the day

of Bolololi. Villagers also voluntarily pile up their

own yams or taro to help the central figure.

Bolololi is performed on the ritual ground called

sara and the feast after Bolololi is held in the meeting-house called gamali. The ritual ground as well as the meeting-house

are said to be possessed by men who already

entered the vira grade, namely, chiefs (ratahigi). Although there are some villages with

plural meeting-houses, generally there is

only one meeting-house in a village. Since

there are usually multiple chiefs in each

village, the meeting-house is said to be

commonly owned by these chiefs. The central

figure of Bolololi is counseled by these chiefs concerning

what kind of insignia he will purchase, what

grade he will enter, and so on. Some of these

chiefs play important roles in Bolololi such as by explaining the class of pigs and

informing people of the gpig nameh (iha boe) of the central figure when he kills the

pig. The pig name is associated with the

name of the grade and is given to a man whenever

he kills a pig to enter a certain grade.

For example, if a man kills a pig and enters

the grade of moli, he is given a name such as Molgaga, Molmemea,

Molture, and so on. If the grade is tari, the pig name may be Tarihala, Tariliu,

and so on. The chiefs playing roles in the

ritual direct the proceedings and also must

give formal approval to the central figure.

In Bolololi, several kinds of dances are performed in

the beginning of the ritual. This is followed

by the stage of boemwarovo, meaning ga pig runs.h In this stage,

many men run slowly on the ritual ground

in a zigzag fashion to the rhythm of the

slit-drums. They are the men who will give

pigs to the central figure. Here, I call

them gpig-givers.h The central figure does

not provide all of the pigs used for insignia

payments and killing to enter the upper grade.

Even if the central figure has enough pigs

to use in the ritual, he should receive pigs

from many men during the ga pig runsh stage.

The stage of ga pig runsh is then followed

by the stage of killing pigs and of purchasing

insignias.

A man who holds the first Bolololi is in the grade of moli. When he wants to enter the grade of livusi, it is necessary for him to kill one pig

of class E. If a man of livusi enters the last grade, vira, he should kill one pig of class F. Killing

only one pig to enter the upper grade is

a minimum requirement, and men try to kill

more pigs than is required because the more

pigs a man kills, the more prestige he can

accrue. The pigs are beaten to death. This

action was, in the past, associated with

acquiring the supernatural power called rorongo. People believed that the more they killed

pigs, the more supernatural power they obtained.

Today, this belief is disappearing. However,

it is still considered praiseworthy for a

man to destroy his valuable goods (that is,

he kills his pigs) and give them as meat

to people at the feast after the ritual.

A man who killed only one pig to enter the

upper grade would be subject to ridicule.

Before entering the vira grade, sese is required. Sese refers to the killing of 10 pigs of any

class. Even if a man of the livusi grade kills eight or nine pigs, this is

not considered sese. After entering the grade of vira, a man cannot enter a higher grade no matter

how many pigs he kills. However, a chief,

who is of the vira grade, will aim to kill 10 pigs of class

E, which is called mabuhangvulu. With this, the chief attains a higher rank.

The word loli within Bolololi means gto perform.h In Bolololi many spectators surround the ritual ground,

and it is necessary for a man to reveal his

rank and display his power in front of many

spectators.

In the past there were five grades and the

number of the pigs to be killed was much

greater than today.4 This is shown in Table 3. Great chiefs in

the past who killed more pigs came up with

new pig names for themselves. As mentioned

above, a man in vira cannot rise to a higher grade, regardless

of the number of pigs killed. Thus the pig

name associated with the grade does not change.

If new names are acquired by killing more

pigs, these names are not associated with

the name of the grade. For example, two such

names are famous today. One is Huhunganvanua

and the other is Tunggorovanua. The former was a name that was

chosen by the chief Viradoro. Viradoro is

a proper pig name. After Viradoro entered

the grade of vira, he kept killing pigs. He finally named

himself Huhunganvanuau, meaning gthe peak

of the island.h The latter name Tunggorovanua, meaning gto stand shutting out

the island,h is that of the chief Viramasoi.

These names are so famous that some people

today think that they are names of grades

that are even higher than vira.

Table 3 Grade and pig killing in the past

|

grade

|

pigs to be killed

to enter the grade

|

specific pig-killing while

in a particular grade

|

|

|

class

|

number

|

name

|

class

|

number

|

|

tari

|

B bololvaga

|

1

|

-------------

|

-------------

|

------

|

|

moli

|

C tavsiri or

Dbobibia

|

1

|

sese

|

any

|

10

|

|

udu nggarai

bangga

|

E mabu

or

F livoala

|

1

|

-------------

|

-------------

|

-------

|

|

livusi

|

any

|

10

|

-------------

|

-------------

|

-------

|

|

vira

|

higher class than C tavsiri

|

10

|

Bohudorua

|

any

|

100

|

|

|

|

livohangvulu

bobibiahangvulu

livbwanbwanahangvulu

mabuhangvulu

livoalnggolehangvulu

livoaltavagahangvulu

bovtagahudorua

livohudorua

|

higher than C tavsiri

D bobibia

E livbwanbwana

D mabu

F livoalnggole

G livoaltavaga

higher than B

bololvaga

higher than C

tavsiri

|

10

10

10

10

10

10

100

100

|

3 Giving and Taking of Pigs

Bolololi is also called gbisines pigh in Bislama, Vanuatu Pidgin. It is called

gpig businessh because in Bolololi the giving and taking of pigs is the main

theme of the stages of ga pig runsh and

purchasing insignias. Here I explain the

giving and taking of pigs in the stage of

ga pig runs.h

In this stage, the pig-giver, after running

in zigzag fashion on the ritual ground, stands

at one end of the ground with his pig. He

tells the class or the kind of the pig to

the central figure. He also tells him gthe

way of giving.h There are basically two

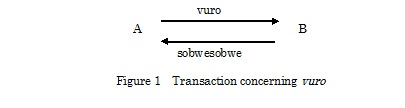

ways of giving pigs: vuro and bugu. If the pig is given as vuro, the pig-receiver should give back a pig

of the same class in the stage of ga pig

runsh of future Bolololi of the pig-giver. Because of this, vuro is often translated as a debt. The return-giving

is called halavuro or sobwe, and the latterfs noun form is sobwesobwe or sobwesobweana (Figure 1). If the novice, namely, the central

figure of the Bolololi formerly gave pigs as vuro in the Bolololi rituals of several men, these men may return

pigs now as sobwesobwe in the stage of ga pig runs.h It is not

certain whether they will return

pigs in this Bolololi because the date of the returning is not

fixed

although the returning is obligatory. Moreover

even if the pig-giver asks the pig-receiver

to give back a pig, the latter often declines

saying that he has no pigs with him. A man

who decides to hold Bolololi usually asks men to whom he gave pigs as

vuro to return pigs as

sobwesobwe. However, it depends on the intention of

the pig-receiver whether he will return a

pig as sobwesobe. Therefore, it is not until the man whom

he gave a pig as vuro starts to run on the ritual ground in the

ga pig runsh stage that the central figure

knows that the man is returning a pig as

sobwesobwe. Additionally, the central figure of Bolololi only expects that pigs will be given as

vuro. In this case too, only when a pig-giver

starts to run on the ritual ground does the

central figure know that they are making

vuro.

When a pig of class B (bololvaga) is given, the pig-giver usually says in

a loud voice, gYour debt is bololvaga (Vuromwa bololvaga).h But he sometimes says, gYour masa is bololvaga (Masamwa bololvaga). h5 Masa means a pig that should be killed. Although

it depends on the intention of the pig-receiver,

namely the central figure of the ritual,

whether a pig given simply as vuro may be used as payment for insignia or killed

in order to enter the upper grade, a pig

given as masa should be killed in the ritual. If the central

figure wants to use this pig as the payment

for insignia, he should get the permission

of the pig-giver. Even if the pig is sobwesobwe, namely a returned pig, it can be appointed

as masa and the right of how to use it is preserved

by the pig-giver. In a Bolololi I observed, a man brought a pig as sobwesobwe and appointed it as masa. The central figure of the ritual (the pig-receiver)

wanted to use it as a payment and negotiated

with the giver. But the negotiations broke

down and the man took back his pig. The central

figure wanted to use the masa pig for payment because he otherwise lacked

a pig of the class needed to purchase the

insignia. This happens because, until the

ritual starts, the central figure cannot

know how many and what kinds of pigs will

be given as vuro or given back as sobwesobwe.

A pig given as bugu is different from a pig of vuro and is brought without fail to the ritual

ground on the day of Bolololi. This is because a pig of bugu is requested in advance from a particular

man, who agrees to bring the pig on the day

of the ritual. On the night before Bolololi, a feast to drink kava is held in the village

meeting-house. At that time, the man who

was asked to make bugu would be the first to drink kava, showing

that he is a bugu-giver. The pig given as bugu should be of a class higher than class D.

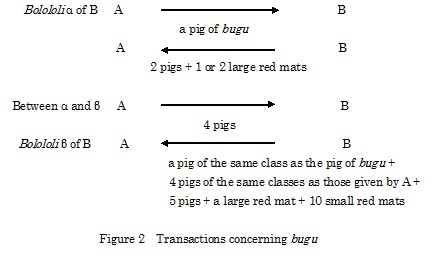

The giving of a pig as bugu should be returned but the manner of return

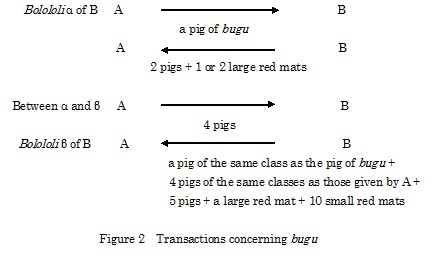

is completely different from that of vuro. Suppose the bugu-giver is A, the bugu-receiver is B, and the Bolololi of B is ? (Figure 2). First, A runs on the

ritual ground in the stage of ga pig runsh

of Bolololi ? and gives a pig as bugu to B. Then in the latter stage of Bolololi

?, B gives two pigs and one or two large

red mats to A. This is the first counter-giving

to the bugu-giver. The two pigs are respectively called

tautau (meaning gto puth) and laitali (meaning gto give a rope tethering a pigh).

The red mat is called tavwen gana (payment for a bait). It is said that the

payment for a bait is a necessary token of

gratitude because much care is needed to

breed and raise a pig with very big tusks.

The class of these pigs and the number of

red mats depend on the class of the pig of

bugu (Table 4).

At some time after Bolololi ?, B holds a Bolololi. Suppose this Bolololi is ?. Between ? and ?, A gives four pigs

to B. This is called sariboe (meaning gto poke a pigh). If A gave two

pigs to B in Bolololi ?, the number of sariboe pigs is three. In this way, B would receive

5 pigs before his Bolololi ?. Then in Bolololi ?, B gives 10 pigs, one

large red mat, and 10 small red mats. This

is the second counter-giving to the bugu-giver. Of the 10 pigs, five pigs are of

the same class as the pigs given by A. The

class of the other five pigs is said to become

higher if the class of bugu is higher. In fact, however, it depends

on the number

Table 4 First counter-giving for bugu

|

bugu

|

pig of class F

|

pig of class E

|

pig of class D

|

|

tautau

laitali

tavwen gana

|

pig of class E

pig of class C

2 large red mats

|

pig of class C

pig of class B

1 large red mat

|

pig of class B

pig of class A

1 large red mat

|

and the class of pigs that are given to B

on the day of the ritual and it would not

be proper for A to complain about the class

of these five pigs. The ten pigs are tethered

to 10 sticks that have been driven into the

ritual ground. If it is the first time for

B to give 10 pigs to the bugu-giver, the 10 pigs are tethered to 10 trunks

of cycad palm driven into the ritual ground.

This is called mwelvavunu.

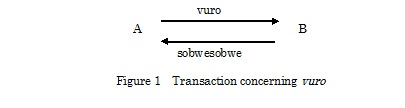

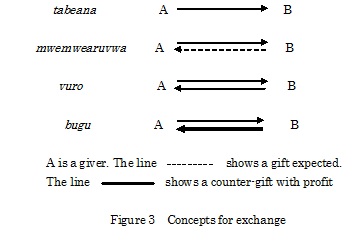

4 Reciprocity

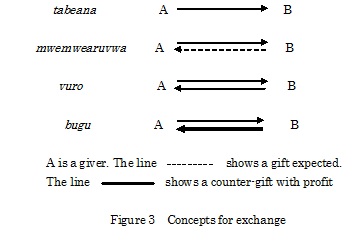

There are mainly four concepts for exchange

in the Raga language, tabeana, vuro, bugu, and mwemwearuvwa, the last of which was described in detail

in The Story of Raga III. These four concepts

are shown schematically in Figure 3. Although

for tabeana, a counter-gift of any kind is neither required

nor expected, a counter-gift of an equivalent

value is expected for mwemwearuvwa. For vuro it is obligatory whereas for bugu it is necessary to pay it back with a big

gprofit.h In the case of tabeana, the relationship between the giver and

receiver is finished when the gift flows

unilaterally, for the counter-gift is not

settled. When a receiver thinks that he or

she gives back something to the giver, a

new flow of tabeana begins. In the case of mwemwearuvwa, a counter-gift is expected but it does

not become a complicated matter if the counter-gift

is not actually given. The relationship between

the giver and the receiver continues for

longer than for tabeana, but may be shorter than vuro for which a counter-gift should be given.

These three categories of tabeana, mwemwearuvwa, and vuro, although schematically differentiated,

are actually intertwined. There are some

cases in which a thing given as tabeana is regarded by the receiver as mwemwearuvwa while a thing of mwemwearvwa is thought of as vuro. Such treatments are said to be proper because

the relationship between the giver and the

receiver will continue for a longer time.

In North Raga the spirit of reciprocity is

very important in peoplefs lives. Reciprocity

or mutual aid is expressed by the word mwemwearuana. The intertwining of these concepts explained

above is thought to strengthen mwemwearuana, the reciprocity or mutual aid. Tabeana may be considered a kind of mwemwearuana because it is done in order to help the

receiver. Vuro, namely the debt, is also regarded as the

starting point of the relationship of mwemwearuana and the counter-gift to the vuro, that is, sobwesobwe is also thought to be a kind of mwemwearuana.

Different from these three kinds of exchange,

bugu is used only in the case of pig-exchange

in Bolololi and seems to be independent from the above

three concepts. However, it is possible to

find the concepts of tabeana, mwemwearuvwa, and vuro in the giving and taking of bugu. The first counter-giving to the bugu-giver is composed of two pigs and red mats.

These two pigs (i.e., tautau and laitali) are said to have the same character as

tabeana. These pigs are given without requiring

or expecting a counter-gift. After that,

four pigs are given to the bugu-receiver and pigs of the same valuation

as these pigs and the pigs of bugu should be given back. This is the manner

in which vuro proceeds. Furthermore, the 10 pigs in the

second counter-giving are called boen mwemwearuvwa (pig of mwemwearuvwa). A man explained this to me as follows:

gThese pigs will go back in the future to

someone in the village of the man who received

the pig of bugu or someone in the same kin group as the

man. If the man who gave the pig of bugu could not give back 10 pigs to the bugu-receiver, the son of the former may do so.

This is not the rule. This is the same case

as that in which if you are given food, you

may give it back sometime. It does not matter

if you do not do so.h The character of mwemwearuvwa is clearly expressed here. The 10 pigs given

in the second counter-giving to the bugu-giver are also called nodaru gai profet, borrowing the word of profet from Bislama. This means gsticks of profit

for the two of us.h It is noteworthy that

the profit is thought not to go to one person

(i.e., the bugu-giver) but is shared by two persons, the

bugu-giver and the bugu-receiver. This also expresses the character

of mwemwearuvwa.

Now, we can consider these concepts of exchange

found in North Raga in relation to the three

kinds of reciprocity, namely generalized

reciprocity, balanced reciprocity, and negative

reciprocity, proposed by Sahlins (1972:193-195).

These concepts of reciprocity seem to be

complementarily related to each other at

first glance, but closer examination reveals

that they are not. According to Sahlins,

the generalized reciprocity varies from a

pure gift to a gift for which a counter-gift

is expected. The gift for which the counter-gift

is required is excluded from this kind of

reciprocity. The excluded gift now seems

to be included in the concept of the balanced

reciprocity. However, the balanced reciprocity

proposed by Sahlins is applied to the gift

for which the equivalent counter-gift should

be made gwithin a fixed period.h The gift

for which the equivalent counter-gift should

be made gat some time in a future,h like

vuro, is excluded from this concept. The third

concept, negative reciprocity, applies when

one receives a gift unilaterally, such as

through an act of haggling or plunder. This

may, at first glance, seem like the inverse

form of generalized reciprocity, but this

is actually not the case because this concept

applies only when elements such as hostile

relations between the giver and the receiver

occur.

Tabeana in North Raga is a kind of pure gift and

can also be considered a kind of generalized

reciprocity. But since this reciprocity is

also applied to the gift for which a counter-gift

is expected, mwemwearuvwa seems to be the best case. However, in fact

it is not the case because mwemwearuvwa swings between two extreme cases, one of

which is tabeana for which the counter-gift is not settled

and the other of which is vuro for which the equivalent counter-gift is

obligatory. As mentioned, vuro is not encompassed by the concept of balanced

reciprocity because the counter-gift for

vuro is not given within a fixed period. The

time when the counter-gift is made depends

on the intention of the vuro-receiver. In contrast, bugu has the same character as the incremental

gift-giving (Gregory 1982:54) or profit-making

exchange found widely in Papua New Guinea

(Strathern 1971, 1983). Is the profit-making

exchange explained by the concept of negative

reciprocity? According to Sahlins, the negative

reciprocity is found in the case of haggling

or plunder and comes in effect between persons

with remote relationships such as hostiles

(Sahlins 1972:196-204). However, bugu in North Raga or the profit-making exchange

in Papua New Guinea is not made between hostiles

but rather between relatives or friends.

In this way, the three concepts of reciprocity

proposed by Sahlins are not applicable to

the concepts of exchange found in North Raga.

5 First Bolololi

As described above, the first Bolololi is a ritual in which a man in the grade

of moli purchases a special insignia. This insignia

is a string of beads made of shell, which

is called bani. The following description is mainly based

on field data concerning a Bolololi ritual that was conducted in Labultamata

village in 1981.

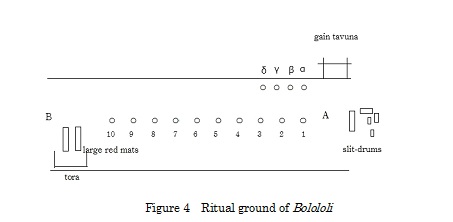

In the ritual, men first perform three kinds

of dances called bolaba, tigo, and mantani, respectively. The first two are performed

to the accompaniment of slit-drums, whereas

the last is danced to a rhythm made by beating

a bundle of bamboo shoots. These dances are

followed by the stage of ga pig runs.h

First a conch shell is blown. Then men beat

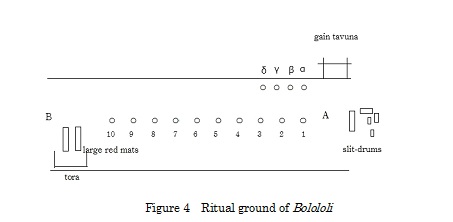

slit-drums and a man starts to run on the

ritual ground. If he comes to the ground

from side A in Figure 4, he first runs straight

ahead on the fringe of the ritual ground

to side B. He then runs slowly toward side

B in zigzag fashion in the middle of the

ground to the rhythm of the slit-drums. He

repeats the same actions twice.

It depends on the man whether the running

starts from side A or B. If two men start

to run simultaneously from sides A and B,

each runs straight on each side of the edge

of the ground. They then run in a zigzag

fashion, crossing each otherfs paths on

the way. People think of this running as

a kind of dance. After running they stand

at the end of the ground with their pigs.

The central figure of the ritual is usually

led in by a man of a higher grade. These

two men run slowly in zigzag fashion toward

the man who is standing with his pig. Then

the sounds of slit-drums stop and the pig-giver

describes his pig. After his speech, the

two men go around the pig-giver a few times

in counterclockwise direction and touch the

hem of his clothes. Then they take the pig

away. The slit-drums start to be beaten again

and another man begins to run.

Those who run on the ritual ground run to

the rhythm of the slit-drums. Although it

is not known who will run on the ritual ground

until a man actually starts to run, the rhythm

of the slit-drums is different from man to

man. The leader of the drummers decides on

the rhythm after he sees who has begun to

run. There are given rhythms for the slit-drums.

In the case of the Bolololi in which a string of beads is purchased,

the first runner should run to the rhythm

of bolaba. The rhythms of other men depend on their

insignias. A man who has not yet obtained

a string of beads should run to the rhythm

of bolaba or gaintavuna. A man who purchased a string of beads in

a Bolololi ritual can run to the rhythm of tigo or the same ranked rhythm, for example,

silonstima. However, if a man wants to run to the rhythm

of gori or manga, he should make a special payment for it.

The rhythm of the slit-drums is a kind of

insignia. Those who run in the stage of ga

pig runsh usually put a leaf ornament on

their backs. This leaf ornament is also a

kind of insignia, which I will further explain

in Section V of this Introduction.

When a man is running in the zigzag fashion,

women sometimes rush from the spectators

to the man and begin to run behind him. This

is a kind of joking conduct called bwaraitoa (see The Story of Raga III), and the women

are the manfs fatherfs sisters. During

their running, some women also come out from

the spectators and hand out small red mats

or hang them on the shoulders of women who

are running on the ritual ground. These women

are the sisters or classificatory mothers

of the man. This action is called langgasi.

After the first runner finishes running,

the central figure of the ritual goes to

the place called tora (see Figure 4). This is done only in the

Bolololi of purchasing a string of beads. The central

figure receives a cycad palm leaf at tora. When a man kills pigs in Bolololi, the pigs are tethered to the trunks of

cycad palms. The action in the tora shows that he is purchasing the right to

use the trunk of the cycad palm in Bolololi. The pig given by the first runner is used

for the payment for this leaf. After many

men finish running, the last runner starts

to run. He is the giver of a string of beads.6

After running, the bead-giver stretches his

right hand aloft on which a string of beads

hangs. The central figure approaches him

and from the back he takes the beads.

The stage of ga pig runsh is over and the

central figure goes to the tora again, where he makes the payments for bolaba and tigo dances. A large white mat that has been

hung on the bar of wooden framework called

gain tavuna is now laid down in the tora. The central figure stands at the entrance

of tora. A ratahigi, namely a chief, gives a speech concerning

tora. In front of the central figure there are

two large red mats, each of which is used

for the payment for bolaba and tigo. A classificatory father of the central

figure who was asked to perform the bolaba dance is called and given a red mat that

is then put on the head of the central figure.

This action is called huni or hunhuni (see The Story of Raga III). Another classificatory

father who was asked to perform the tigo dance is also given a red mat in the same

manner. A white mat is given to the giver

of a string of beads. There are three dances:

bolaba, tigo, and mantani. The payment for the mantani dance is made during the dance. A large

red mat is given to a classificatory father

of the central figure in the manner of huni.

Next is the first counter-giving to the bugu-giver. The central figure of the ritual,

that is, the bugu-receiver gives two pigs and red mats to

the bugu-giver. In the ritual ground, two sticks

are driven into the ground and a pig is tethered

to each stick. If a pig is not brought to

the ritual ground for some reason, a leaf

of varisangvulu is bound around the stick. Although a pig

of tautau and a pig of laitali are counter-gifts to the bugu-giver, the central figure usually purchases

some kind of insignia with the pig of tautau or laitali from the bugu-giver. In the first Bolololi, it is usual to purchase the right to use

a leaf of varisangvulu as a back ornament; the purchase is made

with a pig of tautau from the bugu-giver. In other words, a pig of tautau is used for the counter-gift as well as

for the payment for a leaf insignia.

Next is the stage of the payment for a string

of beads called bani. Ten sticks are driven in the ritual ground

and a pig is tethered to each stick. A chief

explains about these pigs. The central figure

stands at one end of the row of sticks and

the man who gave the beads in the stage of

ga pig runsh dances (running slowly) toward

him to the rhythm of the slit-drums. The

bead-giver has a kind of croton called hahari moli, a leaf called sese adomae, and the red tip of the leaf of sago palm

called bibitanggure in his hands and a feather of a barn owl

called irun visi on his head. These three kinds of leaves

and the feather are also given to the central

figure along with a string of beads. Ten

pigs, two large red mats, and 10 small red

mats are paid for these insignias. Table

5 shows the general classes of pigs used

as payment for the string of beads. The pig

tethered to stick 1 is the payment for the

beads (gaiutun bani) and should be of class D. The pig at stick

2 is called gthe substitute for the pig

to be killed (matan masana).h This pig is of the same class as the

pig killed by the central figure to enter

the grade of livusi in this Bolololi. The man who gives the string of beads also

gave a pig to be killed in this Bolololi. That is, he gave a pig as masa (and also as vuro) to the central figure of the ritual in

the stage of ga pig runs.h

Table 5 Payment for the string of beads

|

stick

|

the class of the pig

|

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

D

higher class than E

B or A

B

C

B

B

B or A

B or A

B or A

|

The central figure killed a pig to enter

the grade of tari and another pig to enter the grade of moli. These pigs were given by his real father

or classificatory fathers. It is said that

these pigs are tabeana of the father. The father who gave those

pigs, in this turn, becomes a giver of beads.

Since he comes with a pig that the central

figure will kill to enter the grade of livusi, the former gives, in total, three pigs

to the latter. It is said that the first

two pigs are tabenana and the last pig is vuro. Tabeana is a gift to which a counter-gift is not

expected. A pig given as vuro is refunded as matan masana as noted above.

After the stage of the payment for the string

of beads follows the stage of pig-killing.

In the case of the Bolololi held in Labultamata described here, the

central figure killed four pigs. In the ritual

ground, four trunks of cycad palm were driven

and pigs were tethered to them. Men began

to beat the slit-drums and the central figure

whose body was painted red, the upper grade

man who led him, some of his sisters, classificatory

mothers, and classificatory fathers who followed

him all ran in zigzag fashion to the rhythm

of the slit-drums. When he killed one of

the pigs, a chief stated his pig name in

a loud voice. The same was done for the other

pigs. The pig name he got when he killed

pigs that were tethered to cycad palms ?

(class C), ? (class E), and ? (class D),

was Udulalau, and when he killed the last

pig ? (class F), he was named Livusiliu (See

Figure 4). After that he was known as Livusiliu.

6 Payment for Insignias

The insignias other than those purchased

in the first Bolololi are mainly classified into three categories.

One is a category of dress composed of, from

the lowest to highest value, a white skirt

woven of pandanus leaves named mahangamaita, a red skirt woven of pandanus leaves named

tamanggamanngga, and a colorful belt woven of pandanus leaves

set with shells named garovuroi. These were originally articles of clothing

to be worn when a man killed pigs. A white

skirt should be put on when a man made first

sese, a red skirt when he killed 10 pigs to enter

the vira grade, and a colorful belt when he killed

10 pigs of class E, namely mabuhangvulu.

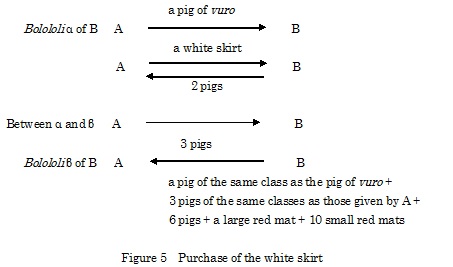

The same method of payment is applied to

all these dress insignias. Here, I describe

a case of the purchase of a white skirt.

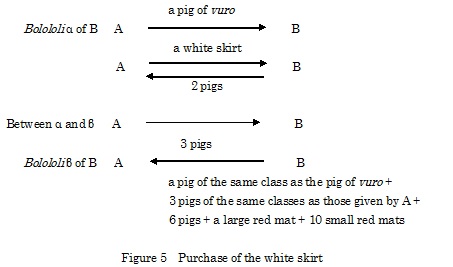

Suppose the giver of the insignia is A and

the receiver is B (Figure 5). When B thinks

that he will purchase a white skirt in the

Bolololi, he looks for a man to give it to him and

gets his agreement. On the day of his Bolololi ?, A gives a pig to B as vuro in the stage of ga pig runs.h In the latter

stage, A now gives a white skirt to B and

B gives two pigs to A. One pig is called

volin mahangamaita (the payment for the white skirt) and should

be of class D. The other pig is called tohebweresi (to make bweresi: bweresi = decorations made at the four corners of

the bottom of the basket woven of pandanus

leaves) and is usually of class B. Between

Bolololi ? and ?, A gives three pigs to B. If A does

not give a pig in the stage of ga pig runsh

of Bolololi ?, he gives four pigs here. Then in Bolololi ?, B gives 10 pigs along with a large red

mat as well as 10 small red mats to A. These

10 pigs are called boen mahangamaita (pigs of white skirt).

Figure 5 shows a model case, but there are

some cases in which 10 gpigs of white skirth

are given in Bolololi ? or a white skirt is not given in Bolololi ? but will be given afterward. In any case,

the substantial payment for the white skirt

is composed of eight pigs, a large red mat,

and 10 small red mats. For a red skirt and

colorful belt, the manner of payment is the

same, but the classes of the two pigs that

are given first in the Bolololi ? become higher (Table 6). Similarly the

classes of the three pigs given by A between Bolololi ? and ? become higher and the last 10 pigs

also are of higher class. Take an example

of the belt. In a Bolololi I observed, a man A gave four pigs of class

E to B, and in the same Bolololi the former gave the colorful belt to B.

B gave a pig of F which is called volin garovuroi (the payment for colorful belt) and a pig

of E called dovonbovo (to measure onefs hips). In the same Bolololi A gave 10 pigs called boen garovuroi (pigs of colorful belt). These 10 pigs are

usually tethered to 10 sticks but in this

Bolololi only eight pigs were tethered while two bags

were bound to two sticks. These were bags

containing the heads of pigs. It is possible

to pay with the head of a dead pig but the

class of the pig is regarded as one rank

lower (Table 7).

These dress insignias are comparatively durable.

They pass to othersf hands in Bolololi rituals. If a man who has purchased a white

skirt in his Bolololi is asked to give it in someonefs Bolololi, he should part with it. Now he has no actual

article. However, he can have a new skirt

made. His wife will weave a white skirt of

pandanus leaves. If he wants to make a new

red skirt or belt, he should pay a pig of

class E for dyeing a white skirt red or making

a belt. A man who has not purchased such

an insignia in the Bolololi ritual cannot give it to another man in

Bolololi, even if he processes it.

Another category of insignia is leaves. This

insignia shows the right to put a leaf on

onefs back as an ornament when a man performs

dances or runs in the stage of ga pig runs.h

The leaf insignia is categorized as, from

the lowest to highest valuation, varisangvulu, bwalbwale, and maltunggetungge, all of which are from kinds of ti tree.

People reported that the highest valued leaf

is vuhunganvanua, but I never observed the use of this kind

of ti tree leaf as a back ornament. The payments

for leaf insignias are shown in Table 8.

Table 6 First payment for the skirt and the

belt

|

Insignia

|

first pig

|

second pig

|

|

|

name

|

class

|

name

|

class

|

|

white skirt

red skirt

belt

|

volin mahangamaita

volin tamanggamangga

volin garovuroi

|

D

F

F

|

tohebweresi

tohebweresi

dovonvobo

|

B

E

E

|

Table 7 Second payment for the belt

|

stick

|

kind of pig

|

class of pig

|

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

mabu

mabu

mabu

tavsiri

head of livoala

head of bobibia

tavsiri

tavsiri

tavsiri

livoala

|

E

E

E

C

E

C

C

C

C

F

|

Table 8 Payment for leaf insignias

|

insignia

|

Payment

|

|

varisangvulu

bwalbwale

maltunggetungge

vuhunganvanua

|

one pig of class C

one pig of class F

one pig of class F

one pig of class F

|

The last category is that of dance. The dance

insignia may be classified into two kinds,

which I call dance insignia 1 and dance insignia

2, respectively. Dance insignia 1 comprises

several dances performed at the beginning

of the Bolololi ritual. In the first Bolololi, three kinds of dances, bolaba, tigo and mantani, are performed. At the next Bolololi another dance called havwana is performed every time. There is no special

payment for havwana, but gori, havwan lavoa, and havwan boe should be purchased with pigs. A large red

mat is given to the father of the central

figure who is asked to perform a dance every

time such a dance is performed. Dance insignia

2 represents the right to run to a specified

rhythm in the stage of ga pig runs.h As

mentioned above, a man in his first Bolololi can run to the rhythm of bolaba. After finishing the first Bolololi, one has the right to use the rhythm of

tigo. Gori of dance insignia 2 is automatically granted

when the gori dance for dance insignia 1 held in the beginning

of the Bolololi is purchased. The payments for dance insignias

are shown in Table 9

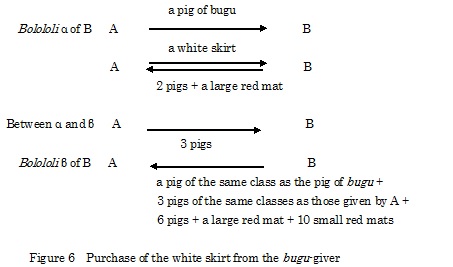

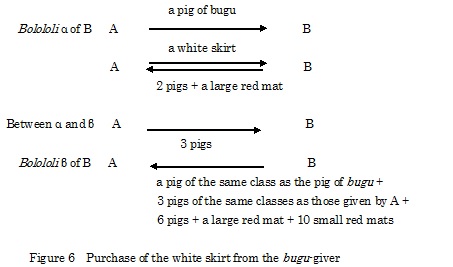

It is noteworthy here that these insignias

are often purchased from the bugu-giver. As an example, I explain the case

of the purchase of a white skirt. Although

the insignia-giver A normally gives a pig

of bugu plus four pigs, in total five pigs to B

(Figure 5), in this case A gives a pig of

bugu, a white skirt, and three pigs to B(Figure

6).

In fact there were some cases in which fewer

than three pigs were given between ? and

?. In contrast, B first gives two pigs and

a large red mat to A. These are tautau and laitali but simultaneously they are also volin mahangamaita and tohebweresi. Similarly 10 pigs serve two roles, one

of which is a second counter-giving to the bugu-giver and the other of which is boen mahangamaita (pigs of white skirt). If the bugu-giver and the insignia-giver are different,

B should actually give seven pigs and mats

to the former and eight pigs and mats to

the latter, in total 15 pigs and several

mats. However, B loses only eight pigs and

mats if B purchases a white skirt from A,

who is at the same time a giver of bugu. Interestingly, people in North Raga do

not seem to care about the difference between

these two cases and the central figure may

attain the same prestige in both cases.

In the case in which a leaf insignia or a

dance insignia is purchased from the bugu-giver, a pig of tautau (one of two pigs given to the bugu-giver)

serves as the payment for the insignia. In

this way, a pig of tautau is used to purchase several insignias. In

a case I observed, a man who had obtained

every dress insignia, every dance insignia,

and two leaf insignias (varisangvulu and maltunggetungge) purchased new insignias with pigs of tautau from the bugu-givers. The new insignias were valen singisingi (a hut of tamtam) and tanbona (a platform in front of the meeting-house).

Whatever insignia is purchased, it is actually

free if obtained from a bugu-giver. Therefore some newly invented insignias

may appear. If another man thinks that it

is a nice insignia, then he may get it in

his Bolololi. Eventually, a personal insignia may become

a public insignia. I wonder whether the two

leaf insignias of bwalbwale and vuhunganvanua were originally personal insignias. Today,

some people think of them as public insignias

but others do not think so.

In North Raga people often use the same thing

as different objects. The feast is a good

example. In North Raga if a man dies, the

funeral ritual is held on the day of the

death, and on every tenth day after the manfs

death a kind of feast or ceremonial dinner

is held by his relatives in each of several

villages.7 Suppose a foreigner visits one of those villages

where a feast is held. If the host welcomes

the foreigner, the funeral feast is also

used as a welcome feast. Suppose two pigs

are killed by a son of the host to enter

the grade of tari and moli and the meat is served as side dishes for

the attendants of the feast. Now the host

can insist that he supplied two pigs for

the side dishes in the feast on the tenth

day of the dead and can also insist that

he offered two pigs to feast the foreigner.

Furthermore it is reasonable for him to insist

that he gave two pigs as tabeana to his son to enter the grade of tari and moli.

Table 9 Payment for the dance insignia

|

dance insignias 1 and 2

|

payment to obtain the insignia

|

payment every time the dance is performed

|

|

1 or 2

|

name of insignia

|

|

1

|

havwana

|

--------

|

a large red mat

|

|

1

2

|

gori

gori

|

a pig of class C

|

a large red mat

|

|

1

|

havanlavoa

|

a pig of class E

|

a large red mat

|

|

2

|

manga

|

a pig of class E

|

------------

|

|

1

|

havan boe

|

a pig of class F

|

------------

|

It does not matter to the people how much

property is consumed gin total.h The important

thing is how much property he could nominally

consume for each event. The man who holds

a funeral feast which also serves as a welcome

feast and who prepares three pigs for the

side dishes in the feast is more praised

than a man who holds two different feasts,

one of which is for the dead man and the

other of which is for a foreigner and who

prepares two pigs for the side dishes in

each feast. The fact that a man can purchase

an insignia from a man who gave him a pig

of bugu can be understood from the same viewpoint.

7 Several Steps of Bolololi

There are several steps in the series of

Bolololi rituals.8 I already described the first Bolololi in detail in which a string of beads called

bani is purchased. Here I will summarize subsequent

Bolololi rituals.

1. Mwelvavunu

A man holds his next Bolololi some years after his first Bolololi. This time, he gives 10 pigs to a man who

gave him a pig of bugu in his first Bolololi. This first giving of 10 pigs to a bugu-giver is called mwelvavunu. Ten trunks of cycad palm are driven into

the ritual ground and pigs are tethered to

these 10 cycad palms.

1)The stage of dance. Usually the havwana dance is done. In some cases, gori dance may be performed.

2)The stage of ga pig runs.h

3)The stage of the first counter-giving for

the bugu that is made this time. Two pigs and red

mats are given to the bugu-giver. If the gori dance was performed, gori as a dance insignia is purchased here for

a pig of tautau. If not, a leaf insignia, maltunggetungge, may be purchased here (the lowest ranked

leaf insignia, that is, varisangvulu, was already purchased in the first Bolololi.)

4)The stage of purchasing a food called gaganiva. Although not obligatory to purchase for

every man, if a man wants this food, it should

be purchased in this Bolololi. Gaganiva is composed of taro, yams, a whole pig,

kava, sugarcane, and coconut fibers. The

payment is made with a pig of class C.

5)The stage of pig-killing. A man who holds

this Bolololi is usually in the grade of livusi. Even if he kills some pigs here, he cannot

enter the vira grade.

6)The stage of giving 10 pigs to the previous

bugu-giver. This is the stage of mwelvavunu.

2. Bolololi in which a man purchases a white skirt and

makes sese.

The central figure here is now in the grade

of livusi. He must kill 10 pigs before he enters the

grade of vira. When a man kills 10 pigs, he should wear

a white skirt.

1)The stage of dance. Havwana dance is performed. If he obtained the right

to perform the gori dance in the previous Bolololi, this dance may also be performed in this

Bolololi.

2)The stage of ga pig runs.h

3)The stage of the first counter-giving for

the bugu in this Bolololi. A white skirt is purchased

with a pig of tautau and laitali.

4)The stage of sese. Ten trunks of cycad palm are driven into

the ritual ground to which 10 pigs are tethered.

A man, the central figure, wearing a white

skirt, kills these pigs one after another.

When a man performs sese, he should give a pig of class B to a man

who already did sese. This giving is called tabe mwelen sese (to lift up a cycad palm for sese). (Tabe or tabeana also means a gift that does not require

a counter-gift.) Usually it is done a day

before Bolololi for sese.

5)The second counter-giving for the bugu that was given in the previous Bolololi. Here 10 pigs are given to the bugu-giver.

6)The state of taboo after Bolololi. A man who killed 10 pigs in Bolololi becomes tabooed (gogona). He should be secluded in the meeting-house

for 10 days. During this seclusion, a man

who is of the same or upper grade prepares

meals for him. He cannot wash his body during

this period. After 10 days, he comes out

of the meeting-house and kills9 a small pig of class A or so. Then he is

released from the state of taboo.

7)Putting a taboo. A man who was released

from the state of taboo, in turn, has a power

to put a taboo on the land. On the tenth

day, a feast is held where a special food

such as a laplap pudding called matailonggon mahangamaita (laplap pudding10 of white skirt) is made. The man gives a

large red mat to a man (or more men, if he

wants) who has already killed 10 pigs wearing

a white skirt. Then a pig of class B or so

is given to the man who took care of the

novice (that is, the central figure) during

his seclusion. After eating the pudding with

men of the same or higher grade, the novice

goes to the land of his kin group and washes

his body. Then he places a taboo to prohibit

anyone taking something for some years from

the plot of land where he washed his body

(Yoshioka 1994:81-82, 1998:218).

3. Bolololi to enter the grade of vira

A man who is in the grade of livui and finished performing sese will hold a Bolololi to enter the grade of vira in order to become a ratahigi, a chief.

1)The stage of dance. Havwana and gori are performed. Sometimes havwan lavoa is made.

2)The stage of ga pig runs.h

3)The stage of the first counter-giving for

the bugu made in this Bolololi. The central figure may purchase the insignia

of the havwan lavoa dance or a leaf insignia with the pig of

tautau.

4)The stage of pig-killing to enter the grade

of vira. The novice may kill some pigs among which

at least one pig of class F is included.

If he did not make sese in the previous Bolololi, he may here kill 10 pigs. If he kills 10

pigs each of which is in class E or higher,

it is called mabuhangvulu. In each case, a pig of class F should be

included. In this way, the pig-killing can

have two roles one of which is that for entering

the grade of vira and the other of which is the prescribed

killing of 10 pigs.

5)The stage of purchasing a branch of Malay

apple (gaviga). This is a characteristic stage of this

step of Bolololi. Vira means a flower. The flower of the Malay

apple is a symbol of ratahigi, the chief. In the ritual ground, a branch

of Malay apple is driven and a large red

mat is put on it. Near it, a stick is driven

into the ground and a pig of class E is tethered.

A chief breaks a small branch of the Malay

apple and puts it on the back of the novice.

He takes the pig of class E and a large red

mat, which are the payment for the branch

of Malay apple.

This pig is called tai gaviga (to cut a tree of Malay apple). This is

a necessary procedure for the novice to become

a chief. He can purchase a branch of Malay

apple with a pig of tautau of the bugu if he does not purchase a leaf insignia

or a dance insignia in stage 3. However,

because the payment for the Malay apple is

a pig of class E or higher, the tautau of the bugu should also be of class E or higher and

thus the pig of the bugu should be higher than class F. In this case,

the pig of tautau is, as mentioned above, called tai gaviga, whereas the pig of laitali is called riv gaviga (to plant a Malay apple). The branch of

the Malay apple should be given by a man

of the grade of vira. If the bugu-giver is not a chief, a chief puts the Malay

apple branch on the novicefs back in the

ritual, but the pigs are given to the bugu-giver. Here, this chief plays his role voluntarily.

6)The stage of second counter-giving for

the previous bugu. If the novice purchased a white skirt from

the bugu-giver, the 10 pigs here serve both as a

second counter-giving and boen mahangamaita (pigs of white skirt).

7)If he kills 10 pigs in this Bolololi, he will get the power to place a taboo.

4. Bolololi to purchase a red skirt and a belt.

A man who has become a chief wants to obtain

a red skirt and a belt. Since he must prepare

many high-class pigs, the number of bugu-givers may increase. Although in the past

a man wore a red skirt when he killed 10

pigs to enter the grade of vira, at present, the red skirt is purchased

after a man becomes a chief.

1)The stage of dance. Havwana and gori are performed. If havwan lavoa was made in the previous Bolololi, it is also performed here.

2)The stage of ga pig runs.h A magnificent

dance called havwan boe, which is performed only by women, is inserted

into the stage of ga pig runs.h This dance

may be performed in this Bolololi or is made in the previous one. After the

dance is finished, payment for it is made

to the organizer of the dance. It is not

possible to pay with pigs of tautatu or laitali.

3)The stage of the first counter-giving for

the bugu in this Bolololi. If there are three bugu-givers, three stages in which the novice

gives two pigs and red mats to the bugu-givers occur. A red skirt or a belt may

be purchased here with pigs of tautau and laitali.

4)The stage of pig-killing. It is not necessary

to kill pigs in this stage, but it is generally

expected.

5)The stage of the second counter-giving

for the previous bugu.

6)The payment of boen tamanggamangga (pigs of red skirt) or boen garovuroi (pigs of belt) is sometimes made here. This

means that the second counter-giving for

the bugu is also made here.

7)A man who is of the grade of vira can put a taboo on the land whenever he

kills a pig in Bolololi. After 10 dayfs seclusion in the meeting-house,

he eats a special laplap pudding called matailonggon tamanggamangga (a pudding of a red skirt) or matailonggon garovuroi (a pudding of a belt).

5. Bolololi of mabuhangvulu

It is difficult for a man to hold this step

of Bolololi using only his own pigs because 10 pigs

whose classes are higher than class E should

be killed. If some of these pigs are given

by others in the stage of ga pig runs,h

these pigs may not be vuro but bugu because they are in a class higher than

E. If there are many bugu, many pigs are used for counter-giving and

their tusks should be big. These pigs are

difficult for the central figure to prepare

by himself and are thus obtained as bugu. The procedure of this step of Bolololi is the same as the previous one. In this

Bolololi, the novice should give a pig of class C

to a man who already made mabuhangvulu, which is called tabe mwelen mabuhangvulu (gift for the cycad palm for mabuhangvulu). The ten pigs to be killed are tethered

to 10 trunks of cycad palm as in the case

of sese.

6. Further steps of Bolololi

Since a man should make the second counter-giving

for the bugu made in the previous Bolololi, another Bolololi will be held. In this Bolololi, a man may kill pigs. Even if he kills pigs

after becoming a chief, his grade as well

as his pig name will not change. However,

when he thinks that he has killed enough

pigs, he may try to give his name as Vuhunganvanua

(the top of the land) or Tunggorovanua (to stand shutting out the island).

In one case, a chief gave his name as Tanmonock,

which seems to be a name from the Central

Pentecost language.

In Bolololi a man is expected to show his strong power

by killing more than the prescribed number

of pigs and by purchasing insignia with more

pigs than prescribed. In fact, chiefs who

kill many pigs are thought to exhibit strong

power. However, not all men can behave like

this. The six steps of Bolololi described above are model cases. Some of

the procedures described in those steps may

be replaced. For example, although people

say that it is not proper to obtain multiple

insignias in only one Bolololi, this actually does occur. In one Bolololi I observed, a man who was in the grade of

livusi but had not yet received any insignias attained

the string of beads called bani, the leaf insignia of varisangvulu, and a white skirt and performed sese, mwelvavunu, and purchased a branch of Malay apple to

enter the grade of vira. In this case, the pig killed to enter the

grade of vira was included in the pigs for sese. He also purchased a white skirt with the

pigs of tautau and laitali, and he made mwelvavunu by tethering 10 pigs to cycad palm trunks,

which served both as the second counter-giving

to the bugu-giver and as pigs of white skirt.

Notes

(1) My field research in Vanuatu was conducted

from August to December in 1974, from April

in 1981 to March in 1982, from August to

October in 1985, from July to September in

1991, from September to October in 1992,

from August to October in 1996, from August

to October in 1997, in September in 2003,

from August to September in 2004, in August

in 2011, in August in 2012, and September

in 2013.

(2) Ratahigi is called jif (chief) in Bislama but is not a gchiefh

as defined by Sahlins. Although the position

of ratahigi is regarded as highly successful, it is

achieved by great effort. A ratahigi may take a middle position between a gbig

manh and a gchief.h But it is different

from a ggreat manh as proposed by Godelier

(1986). For a more detailed discussion, see

Yoshioka 1998 (Chapters 11,12,13,14, and

15) and Nari and Yoshioka 2001.

(3) Kava is called malogu in North Raga and is a kind of Piperaceae

shrub. The sap of its roots is a favorite

drink.

(4) According to Codrington, there are 12

divisions corresponding to the earthen ovens

in the meeting-house. The first five are

ma langgelu, gabi liv hangvulu, ma votu, gabi rara, and woda, which are the inferior steps. The sixth

step moli gis the first that is importanth and contains

three steps. The ninth step is udu, the tenth nggarae, eleventh livusi, and the last vira (Codrington 1891:114-115). Since he said

that the youth in the moli step assumes a name with the prefix Moli, it seems that the last four names (moli, nggarae, livusi, and vira) denote the name of the grade, and the first

five names correspond to the divisions in

the meeting-house. In contrast, Rivers presented

eight names for the grades, tari, moli, bwaranga, osisi, virei, livusi, dali, and vira, stating that only tari, moli, and vira were found at the time of his research (Rivers

1914:210). I did not find the grades named

bwaranga, osisi, virei, or dali in my field research, although I found that

there was once a famous chief named Vireimala.

His grade was vira and he assumed the name with the prefix

Virei. Virei may be another name for the

grade of vira. Dali is used with the prefix of the name of the

grade such as Viradali and may not be the

name of a grade.

(5) In some cases I observed, I found that

each man who gave a pig as masa actually shot an arrow at the pig he brought

to the ritual ground. The arrow was not a

true one but only a twig and was shot using

a makeshift bow. Therefore the arrow did

not puncture the pig, although it is said

that in the past, sharp arrows were used

that actually stuck in the pigs.

(6) In the Bolololi held at Labultamata village, the men who

were not bugu-givers ran as last runners because they

arrived at the village very late. They had

been asked to prepare bull meat for the feast

after Bolololi and the preparations had taken a long time.

(7) North Raga is a matrilineal society with

a rule of avunculocal residence. Since the

land of a kin group is divided into numerous

plots scattered around the whole of North

Raga, the members of the same kin group live

in different places even if they follow the

avunculocal rule. The recent tendency of

virilocal residence also promotes such living

patterns.

(8) I observed every step of the Bolololi ritual during my field research, except

for the Bolololi of mabuhangvulu. The descriptions of Bolololi in this paper are based on data I collected

during my field research from 1981 to 1992.

(9) Here he uses a stone rather than a club

to kill a pig. To kill a pig in this manner

is not referred to as wehi (to kill) but as boha (to throw).

(10) Longgo is a kind of pudding. Grated taro, yams,

bananas, and so on are wrapped in banana

leaves and then baked by means of hot stones

in an earthen oven.

References

Allen, M.H.(ed.)

1981 Vanuatu: Politics, Economics and Ritual in

Island Melanesia. Sydney: Academic Press.

Codrington, R.H.

1891 The Melanesians: Studies in Their Anthropology

and Folklore. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Godelier, M.

1986 The Making of Great Man: Male Domination

and Power Among the New Guinea Baruya (R.Swyer, trans). Cambridge: Univ. Press.

Gregory, C.

1982 Gifts and Commodities. London: Academic Press.

Nari,R. and M. Yoshioka

2001 gLaef Stori Blong Viradoro: Wan long

Ol Las Jif Blong Vanuatu.h. Kindai 88:1-71.

Rivers, W.H.R.

1914 The History of Melanesian Society. 2 vols. Cambridge: Univ. Press.

Sahlins, M.

1972 Stone Age Economics. New York: Aldine.

Strathern, A.

1971 The Rope of Moka. Cambridge: Univ. Press.

1983 gThe Kula in Comparative Perspective.h

In The Kula: New Perspectives on Massim Exchanges .(eds.) J.W. Leach and E.Leach. Cambridge:

Univ.Press.

Yoshioka, M.

1994 gTaboo and Tabooed: Women in North

Raga of Vanuatu.h In K. Yamaji (ed.) Gender and Fertility in Melanesia. Nishinomiya, Dept. of Anthropology, Kwansei

Gakuin Univ. pp.75-108.

1998 Graded Society in Melanesia: Kinship, Exchange

and Leadership in North Raga (in Japanese). Tokyo, Fukyosha.

2003 gThe Story of Raga: A Manfs Ethnography

on His Own Society(III) Marriageh. Kokusaibunkakenkyu 20:47-97.